Astrolabe 34: What Big Robots Teach Us About Being Human

There’s Bones in that Bot

By Emma Mieko Candon

When people met me at 25, the wrongness of my body was immediately apparent. It was the thinness, the frailty, the new scars and fragile veins. Another clue: the walker and its cat-mauled tennis balls. So too the oxygen tank—the fancy kind you keep in a bag that spurts air up the tube into your nose only when you inhale. Tst-tst-tst. Even when I graduated to a cane and a steady gait, I made no effort to hide the red tangle of knotty scars at my throat, though I did my best to contain the chronic cough. (A mistake, BTW. Cover your mouth, but don’t hold it in. Great way to put even more stress on the flesh apparatus.)

I had by then long since been convinced by Donna Haraway’s thesis of cyborg humanity—that we as entities exceeded our flesh the second we developed tool use, and that it got even worse when we introduced the context of gifts and possessions. But as the years go on, the extended thing-ness of my body only grows more apparent. I am artificial and constructed; I am alive because I have been built.

I thought this was what brought me to a fascination with robots and AI—the extension of humanity through embodied machines! But no, my friends said. We remember the whole Gundam thing.

The Machine is a Monster

Right, the whole Gundam thing. About that.

This might sound weird coming from someone who’s just put out a book about beautiful giant robots, but I’ve never really been interested in robots—at least when they aren’t moving. When a giant robot is just standing there/floating in space/being a Gunpla model, a monument to itself, my eyes pass over its silhouette as they would any other large structure. Perhaps I’m impressed by its artistry, or intrigued by the underlying design, but it isn’t really an object of curiosity.

But when that titan lifts its hand? When its leg rises and its foot crashes down—when it turns its arm to reveal the medium of great violence?

Then I am afraid. Then I am fascinated.

I am drawn to large machinery in the way I am to monsters. When I describe something on the magnitude of a spaceship, I know it can be warmth and a home, but it is also, to me, an existential threat of size and speed and impact. My body is all too familiar with its own fragility. I cannot perceive this immensity without thinking of my fundamental physical relationship to it.

I don’t know that I was thinking any of this, even on an intuitive level, when Gundam Wing first stomped into my life—when it was Toonami’s heady alternative to Dragon Ball Z that I was instantly in love with for the pretty boys and twisty political intrigue. Now, though, I am well versed in the brittle nature of my body, and I have been taking new hikes through Gundam: Iron-Blooded Orphans, then more recently (it just finished! go watch it!) Gundam: the Witch from Mercury. Both series are immediately and intimately Gundam at its best:

- an interrogation of exploited bodies in the context of vast systems and machines

- the absurd and precious possibility of human connection.

Ah, right, and 3., the eternal backbone of Gundam as a narrative: War…bad???

The Monster is People

War bad. Seems silly. Pithy. Of course war bad. No one right with their mind, body, or soul wants war.

Do they? Enh. Reality seems to beg to differ. War is happening, right now, all over, in all its ugliness and horror. The great machines of nation, capital, hunger, and hatred grind our smallness through cruelty after cruelty. And for all these great things are the dire mechanisms, it is small human hands that pull the triggers and incise flesh. It is a devouring cycle, it is corrosively sick, we are so pitifully trapped.

I struggle to write this with any kind of resonance or meaning. War bad. Simple, two words, three letters each, and yet abysmally less than the entirety they gesture toward. How many more words would I need? How many more letters and syllables and theories and treatises and grotesqueries must I lay down to properly express war?

Because you have to say something. The nothing is worse. Deadly.

But how? How do you encapsulate the monstrous enormity? How do you even begin?

I don’t know, I don’t know. But I see how some have tried.

The People is the Machine

Giant robots are shockingly silly. They’re physically impossible. They’re often being painted bright LEGO colours or being constructed out of mechanized lions. As often as they’re the centre of gritty stories of human suffering (with a touch of transcendent human connection), they’re goofy warriors for goodness, light, and the power of friendship, taking part in schlocky melodrama. When asked by a stranger what I write about, I say “Oh, giant robots” in the most self-effacing tone. SILLY!

Here’s the thing: this genre has a legacy, at least in Japan. There, mecha stories arrive in the aftermath of World War II, during which Japan both suffered and was the perpetrator of unconscionable violence. And in that aftermath, the Japanese government was (and still is) often eager to honour only its own dead—and to sweep under the rug all the horrors it committed.

How do you live with that? How do you breathe? What do you say?

I don’t think it’s always—or even usually—conscious. Maybe you just find yourself drawn to the idea of samurai and ronin, men of violence bound by rigid hierarchies and honour codes. And maybe you particularly like to write stories where their moral centres are flayed open by the commands of their superiors. “Kill that man,” says the lord. “This doesn’t seem right,” says the samurai—as he kills the man, and then has to somehow goddamn live with it.

Maybe this is what you need to express the overwhelming pressure of complicity and silence.

Or maybe you find yourself thinking in terms of the sheerly absurd. Monsters of incredible magnitude. Robots of like immensity. Maybe you use them to evoke atrocities lived and visited upon your world and body. Maybe it seems only right that they should also dance, that they should be cartoonish caricatures of human experience. Because maybe this metaphor of ludicrous size and self is just the best way to articulate a raw immensity that you cannot otherwise grasp.

Maybe that’s why the robot needs to be larger than the world should ever let it be.

They’re Metaphors, Harold

Small wonder that, when I started writing a book driven by the dissolution of my body, I reached for the magnitude of mechs. It wasn’t intentional. It just happened. Here was an idea perfectly fashioned for a story of total self-destruction and survival. I wasn’t looking to express how I had been let to live because of my artificial hips, or because of the machines that pumped air and blood out of and back into my body. I was trying to capture a giant.

No. That’s not right. I was trying to say that I had been captured by that giant.

No. That’s not right either. I was trying to say that the giant had pulverized me, and that in so doing, it had made me part of it, and that now I live with the tremors of its weight in my every step.

I got so fucking big.

The Archive Undying by Emma Mieko Candon is available now from Tor.com Publishing. Candon is a bestselling author of speculative fiction whose work includes Star Wars: Ronin (2021), a Japanese reimagining of the Star Wars mythos, and The Archive Undying (2023), the first original speculative novel in a series about divine AIs, giant robots made of bone, and fraught queer romance. Find Emma at @EmmaCandon or http://emcandon.com.Out & About

Out & About is where I highlight my work around the web—some recent and some old favourites.

Y’all. I got to write something about Final Fantasy for IGN! Final Fantasy XVI, no less! “How Final Fantasy XVI Redefines the Series Again (And Don't Call It a JRPG)” is exactly what it says on the tin: a thorough (but not exhaustive!) deep dive into Final Fantasy’s history of reinvention, and how labels change over time.

The idea that genre labels have to be binary robs the creative agency of the people who create the games, and the people who are in turn inspired to create something new. As Final Fantasy has proven time and again over the decades since its creation—and as I explore in my 2022 book, Fight, Magic, Items: The History of Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest, and the Rise of Japanese RPGs in the West—genre labels are useful as shorthands to invoke a feeling, but they become less useful, and often harmful, when used to pigeonhole or dismiss work as "this" or "that."

"JRPG" is a vibe. It's a feeling. It's a matrix of inspirations and goals. It's a broad, expanding, and diverse set of themes, inspirations, narrative/gameplay structures that can be used to understand games, but shouldn't be used as an arbitrary label to put them in a clearly defined box.

And now that term may be on the way out entirely. When Yoshida says he doesn't want people calling Final Fantasy XVI a Japanese RPG, he's not deriding the genre's history. He's calling out the western roots, perception, and usage of the word, and encouraging players to think in non-binary terms. Final Fantasy XVI is a character action game, but it's also an RPG, and a cinematic narrative experience, it's got fighting game DNA in there, and, yes, bit inspired by the very first "JRPGs," too. A game can be many things.

IGN was also able to help me reach the Final Fantasy XVI creative team, so I was thrilled to be able to ask producer Naoki Yoshida, director Hiroshi Takai, and scenario writer Kazutoyo Maehiro about the ethos of Final Fantasy, the meaning of “JRPG,” and how series evolve as their audience changes and grows.

There's a perception among some western fans that a Final Fantasy game requires certain elements to qualify as a true Final Fantasy game—a sentiment that also exists among Japanese fans, according to Yoshida.

"You have a lot of fans that maybe don't want the series to change," Yoshida explained to IGN. Sticking too close to a formula, however, runs the risk of becoming stagnant, he continued. "If it's not going to change, then that doesn't give motivation for players that maybe look at the Final Fantasy series as, 'Okay, this is something maybe that's not for me. And it never changes, so why do I even want to try it?'" Once that starts happening, according to Yoshida, "your audience gets smaller and smaller, because you keep making it for the same people."

Read “How Final Fantasy XVI Redefines the Series Again (And Don't Call It a JRPG)” on IGN

Some more

- How the greatest Japanese RPGs of the ‘90s came to the West (Washington Post)

- How Japanese RPGs Inspired A New Generation Of Fantasy Authors (Kotaku)

- Lost in Translation (Unwinnable)

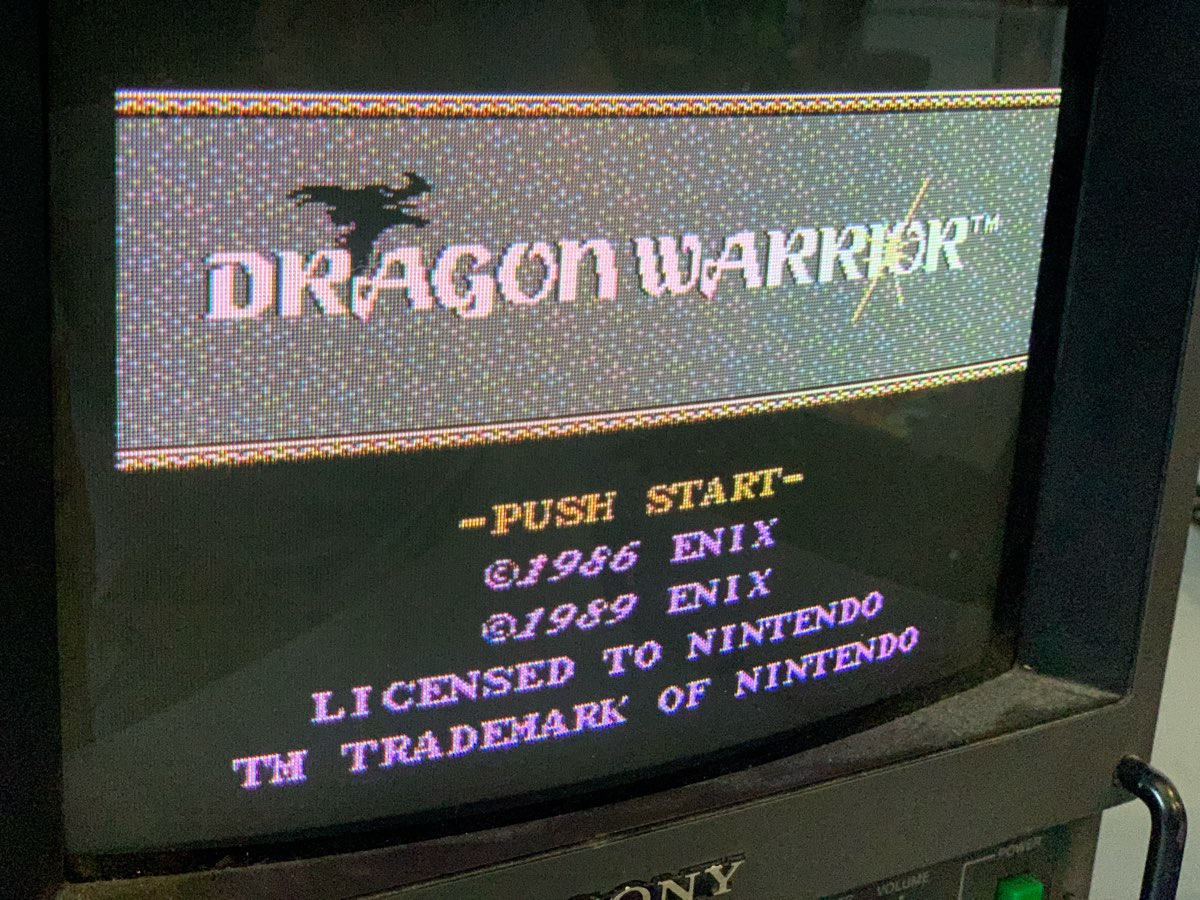

LTTP—Restoring a Nintendo Entertainment System (1983, Nintendo)

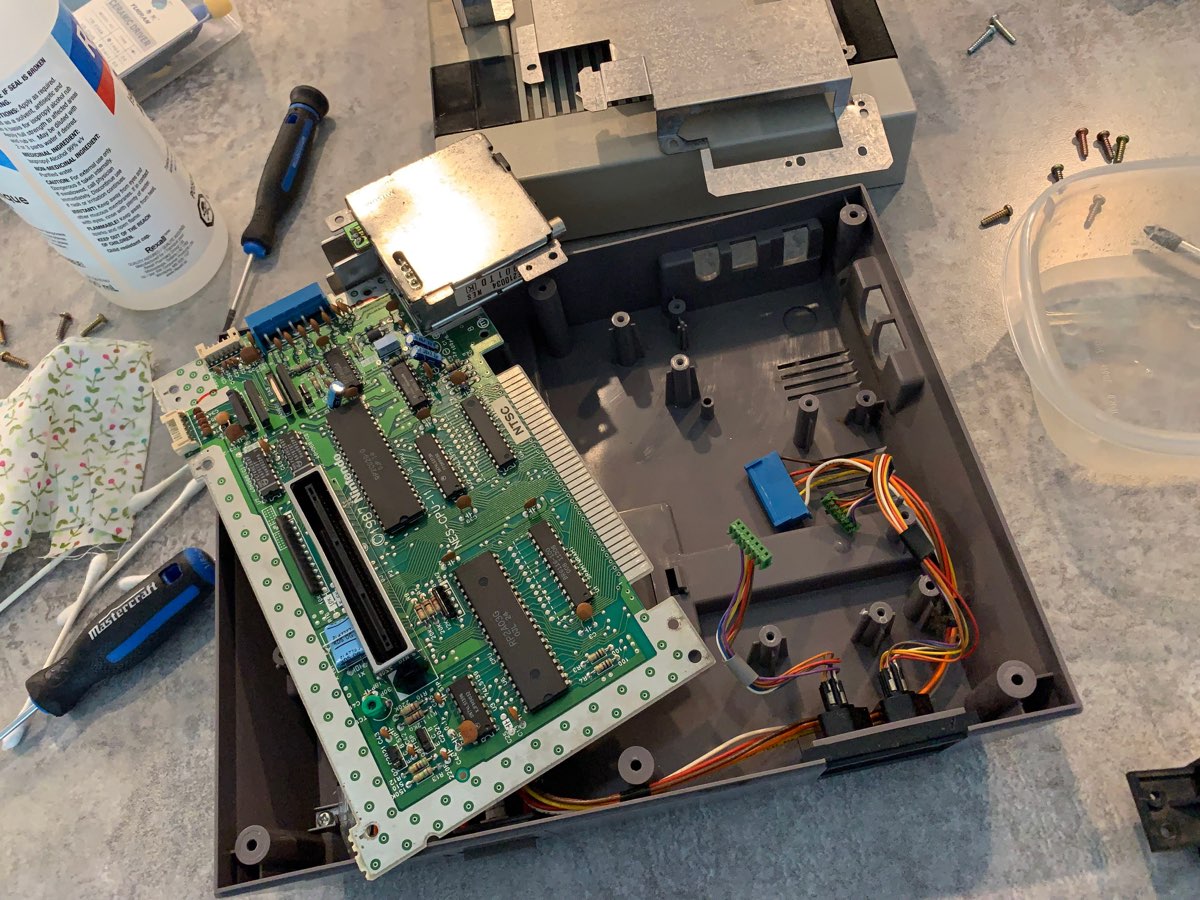

LTTP (Late to the Party) is a regular column where I let Twitter decide which retro game I’ll play for an hour. Do your worst, Twitter!I’ve covered a lot of retro video games in past LTTP entries, but what about an entire console? If you can believe it, I’ve never owned an NES. My family regularly rented one along with Super Mario Bros., Marble Madness, Ducktales, and Chip ‘n Dale when I was a kid, and I’d play extensively at my friend’s house, but by the time I was getting invested in console video games thanks to my Game Boy (I’d been a PC gamer to that point), the Super NES was on the horizon and my parents were savvy enough to understand why it was an essential upgrade.

So, I figured it was time to rectify that and grabbed a broken NES on Marketplace with a bundle of games for $100, along with another lot of games for $150. Highlights include Super Mario Bros. 1 & 3, Ice Hockey, Super Dodge Ball, Tetris, Excitebike, and Tecmo Bowl. A trip to a couple local game stores also netted me gorgeous copies of Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest, Rad Racer, and StarTropics.

Suddenly I’d acquired a decent library of NES games, and I’m not too far out of pocket. Sounds good, right?

“But, Aidan, didn’t you say it was broken?”

Yup!

Fortunately, the seller was upfront and knowledgeable about the issues and provided enough information to make me fairly confident I could fix the issues myself. Anyone with an NES knows about the blinking red light of death which plagued this system. When I first hooked it up, sure enough I was greeted with a blank screen (black, mostly, sometimes a solid colour), and the blinking red light on the front of the console.

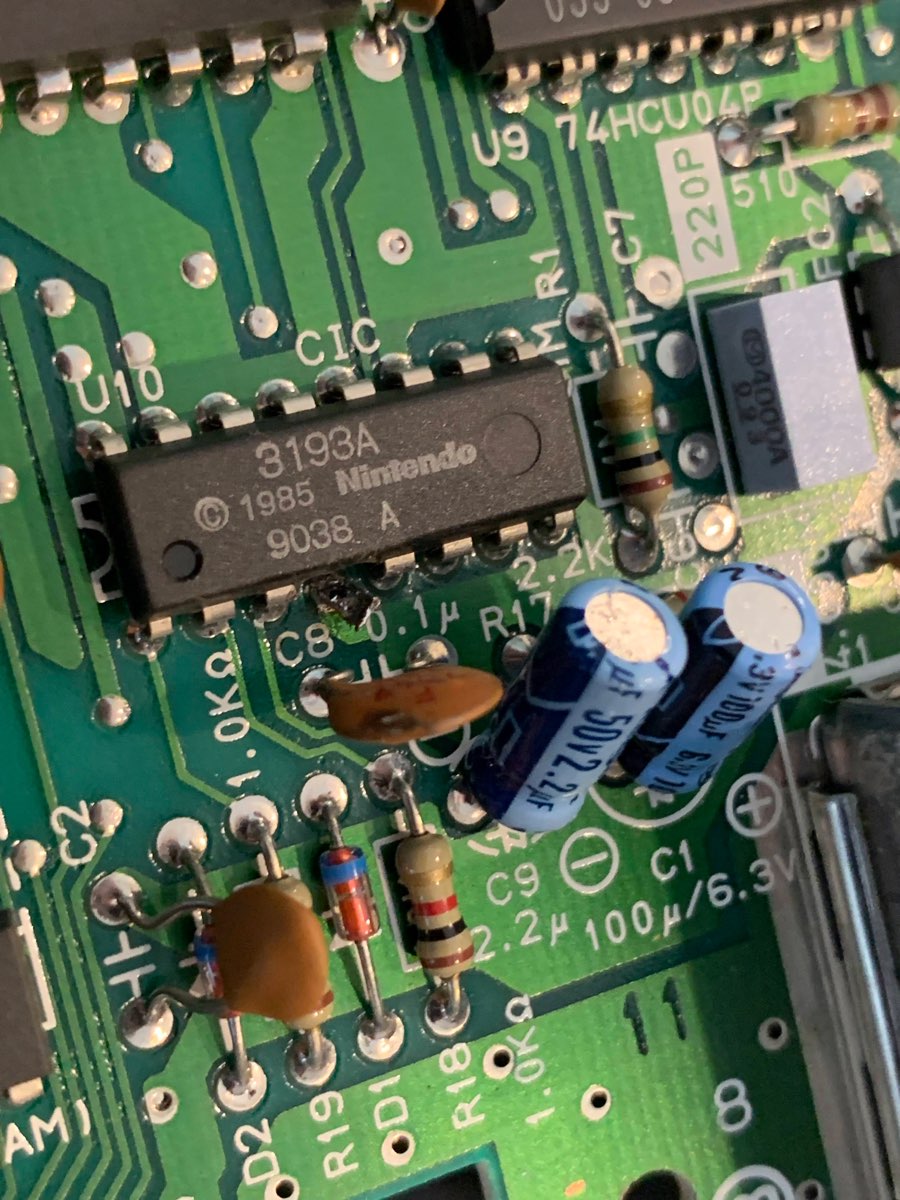

This issue generally results from a malfunctioning 10NES chip. Originally, the 10NES was used as a region lock-out system to prevent people from playing games from other countries. The cart and system each had the same chip, and if they matched, bingo, you’re good to go. If they didn’t, the system would reset itself every second. Overtime, these chips go bad, and the system starts locking out all games, regardless of region.

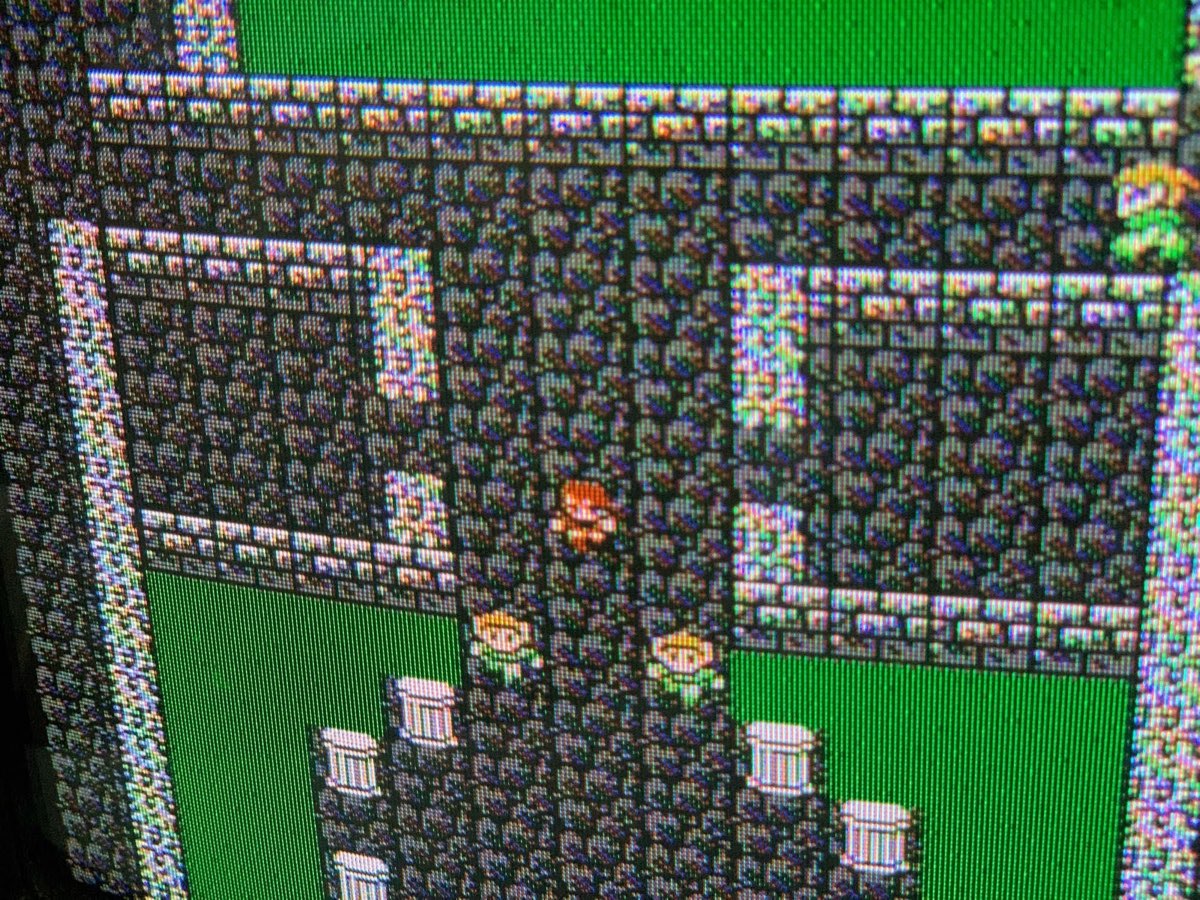

Fortunately, the fix is easy: you just clip pin four on the 10NES chip (seen in the third photo below). With that done, the red light stopped blinking (yay), but… games still wouldn’t load expect for the rare cart that would boot up with garbled graphics (see the first image below). Still work to do.

Because some games would load, even partially, and the light had stopped blinking, I knew I’d resolved that issue, but I still couldn’t play games. The NES is famously finicky—we’ve all had to blow on carts over the years, right? (Don’t do that! Use 70+% isopropyl alcohol and a cotton swap!)—and the 72-pin connectors (the piece the carts slot into) fail regularly, especially after decades of use and neglect.

I hopped on Amazon to get a replacement connector, which looked great when it arrived, but, alas, didn’t resolve the issue (probably shouldn’t have just bought a random one off Amazon, really, but I was impatient). So, I broke out the big guns: a pot of boiling water.

Yes.

That’s correct.

A pot of boiling water.

Turns out that boiling the original 72-pin connector helps clean gunk and corrosion off the contacts, and resets them into their original positions. I disassembled the board, popped the OEM connector in the boiling water—feeling like an idiot the whole time. I was being trolled, right?

While it boiled away, I cleaned the contacts on the main board vigorously with 99% isopropyl alcohol, and then let everything dry.

MAKE SURE YOU LET EVERYTHING DRY COMPLETELY. DON’T CHEAT.

Once everything was bone dry, I partially reassembled the NES, popped in a game I knew was clean (Final Fantasy, which I bought from a game store that cleans and restores all its product), and…

Success! I’m now the proud owner of an NES—my first—and a whole bundle of games to explore with my kids, including long-time favourites and new-to-me classics. As someone with a decades-long relationship with video games, it’s not often I get to dive head-first into an entire console library for the first time, especially one as vastly influential as the NES, but here I go.

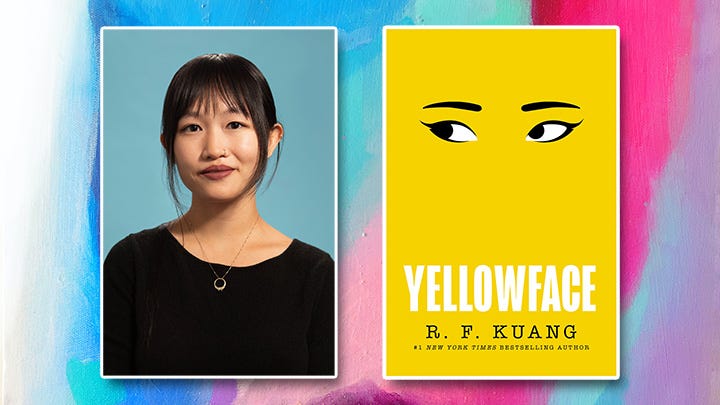

Recommended Reads: Yellowface by R.F. Kuang

Authors June Hayward and Athena Liu were supposed to be twin rising stars. But Athena’s a literary darling. June Hayward is literally nobody. Who wants stories about basic white girls, June thinks.

So when June witnesses Athena’s death in a freak accident, she acts on impulse: she steals Athena’s just-finished masterpiece, an experimental novel about the unsung contributions of Chinese laborers during World War I.

So what if June edits Athena’s novel and sends it to her agent as her own work? So what if she lets her new publisher rebrand her as Juniper Song—complete with an ambiguously ethnic author photo? Doesn’t this piece of history deserve to be told, whoever the teller? That’s what June claims, and the New York Times bestseller list seems to agree.

But June can’t get away from Athena’s shadow, and emerging evidence threatens to bring June’s (stolen) success down around her. As June races to protect her secret, she discovers exactly how far she will go to keep what she thinks she deserves.

With its totally immersive first-person voice, Yellowface grapples with questions of diversity, racism, and cultural appropriation, as well as the terrifying alienation of social media. R.F. Kuang’s novel is timely, razor-sharp, and eminently readable.

Wow.

As a fan of taut, intensely paced thrillers, Yellowface won me over. As a debut author who’s found himself equally enthused and frustrated by the state of traditional publishing, marketing, and writing, Yellowface won me over. As someone who has a lot of learning to do when it comes to appropriation, issues impacting Asian American diaspora and culture, and the siren call of white privilege and outrage, Yellowface won me over and gave me a better understanding of how publishing is hard for (almost) everyone, but even harder for marginalized writers regardless of their success. The more I saw myself and my experiences reflected in protagonist June Hayward, the more I realized the essentially of this novel that challenges its readers while being impossible to put down. Yellowface is a brilliant.

Yellowface by R.F. Kuang is available now from William Morrow.Quest Markers

Quest Markers is a collection of the coolest stuff I’ve read around the web lately.- Gaming's warped mirror (Roadmap)

- The ‘JRPG’ label has always been othering (Polygon)

- Celeste's Five-Year Journey to Becoming One of the Most Important Trans Games Ever (IGN)

- 5 SFF Books About Homecomings (Tor.com)

- How Samuel R. Delany Reimagined Sci-Fi, Sex, and the City (New Yorker)

- Why do games media layoffs keep happening? (GamesIndustry.biz)

- Square Enix ‘Considering’ Remastering More Of Its Long-Lost RPGs (Kotaku)

- The untold history of Barbie Fashion Designer, the first mass-market ‘game for girls’ (Polygon)

- Podcast: Do Pikmin Have Souls? (Remap Radio)

- Searching for a scuff on a stranger's shoe: I found my people and passion on a skateboard (CBC)

- The Making Of: J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, Vol. I - A Middle-earth Classic (Time Extension)

- In Video Games, There’s a Fine Line Between Difficulty and Disrespect (Vulture)

- “We Have Built a Giant Treadmill That We Can’t Get Off”: Sci-Fi Prophet Ted Chiang on How to Best Think About AI (Vanity Fair)

- 'First-Person Shooter' Is An Uneven Yet Fascinating Trip Through FPS History (Time Extension)

- A Fandom of One: Loving the Books No One Else Knows About (Tor.com)

- Super Mario RPG (or, once I was Mallow, a boy of cloud, a boy alone, savior) (Wolf)

- A Chronology of First CD-ROM Games (CD-ROM Journal)

- Final Fantasy IV and the Influences of Baron Munchausen (Art Eater)

End Step

Big robots, tiny lock-out chips, growing video game libraries, and must-read books. This has been a doozy of an issue, and I hope you’ve enjoyed reading it as much as I enjoyed assembling and writing it. On another note, keep your ears open for some very exciting Fight, Magic, Items news coming later this month.

Support

There are lots of ways to support Astrolabe and my other work. Check ‘em out!

Keep In Touch

Enjoy Astrolabe? Want more SFF and retro gaming goodies? You can find me on Twitter and my website.

Credits

Astrolabe banner photo by Shot by Cerqueira on Unsplash

Member discussion