Final Fantasy XVI wants to be the "Game of Thrones" of video games, but is it too late?

"It's the Game of Thrones of JRPGs."

One could go all the way back to Suikoden and Suikoden II (coming soon in remaster HD form to modern consoles) in the late '90s to find the genre’s first “Game of Thrones” with its mix of high fantasy, grounded stakes, and political intrigue. It's an unavoidable mishmash of comparisons meant to symbolize the genre's growing share of adult fans, and a tie to one of the most successful fantasy IPs of all time. But, you can’t make that comparison without also acknowledging that the first Suikoden was released six months before George R.R. Martin’s A Game of Thrones kicked off a two decade-long revitalization of gritty epic fantasy in popular culture.

2023’s Final Fantasy XVI returns the series to its faux-European fantasy roots and, and, in the processes, channels the type of sex and violence-fuelled faux-medieval fantasy closely associated with Martin’s success. Gone are the airships and the technopunk. Gunblades, blitzball stadiums, and highway-cruising convertibles are nowhere in sight, replaced instead by a low-tech setting and a cast of characters bursting with indefinable European accents. It’s a world that feels closer to Hidetaka Miyazaki’s1 ourve than any recent Final Fantasy. In the game’s first several hours, there’s sex, close-up shots of throats being slit, children with blades pressed into their necks, a murder shown through the eyes of the victim, a main female character whose plot conflict is defined by two separate on-screen threats of sexual violence, and enough f-bombs to make even Barret Wallace blush.

Final Fantasy XVI seems to be trying a bit too hard to make a point about how Final Fantasy has changed and grown up, but comes across feeling like a teenager’s idea of mature storytelling.

I discovered Final Fantasy when a baby-sitter brought over a copy of Final Fantasy VI to play after my brothers went to sleep. It was a gateway experience that introduced me to a world that felt dangerous and morally ambiguous without ever crossing the line into anything inappropriate for children. As the series has grown up, so has its audience. Despite Square Enix’s open desire to draw in a new audience with Final Fantasy XVI, it’s explicitly geared towards adults, and far from something I’d be comfortable with a babysitter bringing over to play with my kids while I was out of the house.

It wants so desperately to channel Game of Thrones’s mainstream success, but… does anyone still want that?

Where Suikoden and Martin came to similar simultaneous conclusions about how mixing high fantasy and real history-inspired politicking could gel—taking their respective mediums and genres in new, exciting directions—Final Fantasy XVI is clearly a derivative work. It calls heavily on the television adaptation of Martin’s Game of Thrones with its faux-medieval setting, dark tone, moral ambiguity, huge cast, but also plucks recognizable elements from its own history—you fight a gigantic malboro boss about an hour into the game—and other popular fantasy books and films. The opening scene, where two gigantic “Eikons,” this game’s version of summons, battled it out while plummeting down a dark tunnel, pummelling each other with fiery magic, until eventually emerging into a cavernous opening, is straight out of Peter Jackson’s The Fellowship of the Ring. It doesn’t even pretend otherwise.

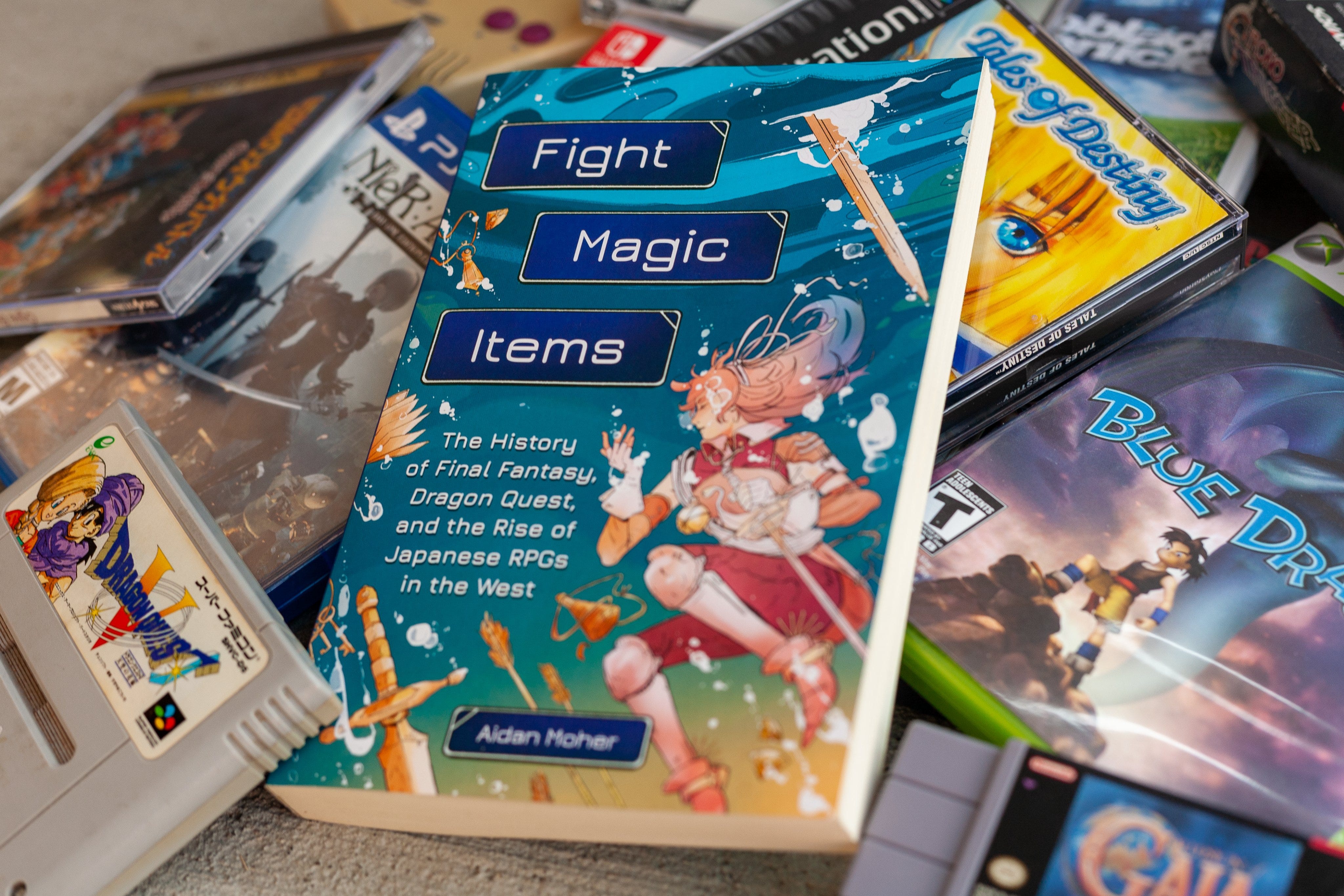

My book Fight, Magic, Items explores how Square Enix’s history with RPGs is deeply entwined with the works of western creators—inspired and inspiring each other with each new game. This sort of cultural exchange—a phrase I nicked from a fabulous conversation with Everybody’s Talking at Once’s Drew Messinger-Michaels—is on full display in Final Fantasy XVI’s opening hours. Hironobu Sakaguchi and Yuji Horii drew on western influences like Ultima and Wizardry when creating their landmark series, but as Final Fantasy evolved, it diverged from its contemporary rival Dragon Quest in its ambition to reinvent itself with each new entry. Some of its most popular titles, like Final Fantasy VII, feel heavily influenced by Japanese anime, and others, like Final Fantasy X, are openly influenced by the development team’s experience working in Hawaii.

I’m not chaste, and I have no moral issue with sex and violence in stories2, but in the first several hours of Final Fantasy XVI it all feels a bit… cheap. They’re going for the shock factor Game of Thrones garnered on its release—but seem to forget that that was 12 years ago and pop culture has moved on. That time has passed, and Square Enix is doing Final Fantasy a disservice by relying on sex and gore to make the game feel “mature,” without backing it up with the complex themes and questions that make a work memorable and thought provoking. I don’t mind sex and violence in games or television if it serves a purpose, but its preponderance in Final Fantasy XVI’s first few hours is trying a bit too hard to make a point about how Final Fantasy has changed and grown up, but comes across feeling like a teenager’s idea of mature storytelling.

Sex and violence are not spices to mix into a story to give it some punch—they’re core, emotionally-driven elements of being human.

2018’s God of War, a game that won critical and fan plaudits for its unexpectedly thoughtful storytelling—felt mature not because of its abundance of violence, but because it took that trait, which was built into the series from its beginning, and examined how it changed its characters. How it affected Kratos as a father. How violence shapes young Atreus during formative years of his adolescence. God of War’s use of narrative violence felt far more “grown up” than the silly fights of a thousand punches between Kratos and the villain Baldur.

In a piece for Kotaku called “I Had My Sexual Awakening Thanks To Final Fantasy X,” Ash Parrish wrote about how Final Fantasy X’s PG-rated sex scene with Tidus and Yuna helped her understand how emotion and sex are tied together. “It is probably the most romantic moment in a Final Fantasy game ever, and it is definitely the sexiest,” Parrish wrote. “Until that point, I understood sex as something people did when they were attracted to each other the same way people ate when they were hungry. It was the satisfaction of a physical, not emotional, need. But Final Fantasy finally linked sex to an emotion I could understand—love.”

Final Fantasy X couldn’t have happened without that scene, which linked the game’s overarching themes with Tidus and Yuna’s emotional journeys.

Sex and violence are not spices to mix into a story to give it some punch—they’re core, emotionally-driven elements of being human. Like magic, if you’re going to add sex and violence to your game, your game needs to tell the player something about sex and violence. It should reveal emotional elements integral about your story and characters. It should be inseparable from the story you’re trying to tell. I‘m not talking about plot-relevant sex (people have plot-non-relevant sex all the time, it’s part of life), but the use of these narrative tools to create and prove whatever point the author’s trying to make outside of “look at this, it’s for grown-ups.”

There’s an interesting scene early in Final Fantasy XVI that shows the potential for a more mature take on Final Fantasy. Speaking in their bedroom, Clive’s father, the Archduke Elwin, rebukes his wife, the power-hungry antagonist Anabella Rosfield, as she tries to persuade him to her side while coming onto him with clear intent to use sex to emotionally manipulate the troubled duke. It speaks to their divided marriage, the way sex and politics can be entwined, and tell us something about Elwin and Anabella. We understand them and their relationship better after we see Elwin refused Anabella’s advances. But, several hours later, this scene remains the exception, rather than the norm, and that only further strengthens my feeling that Final Fantasy isn’t a series that needs these elements to tell its best stories.

Earlier games in the series featured bloodshed and mayhem—like Final Fantasy VI’s Kefka poisoning Doma Castle, or Aerith’s impaling in Final Fantasy VII—but the lower fidelity graphics created a layer of abstraction that allowed the player to interpret those scenes with a level of visceral detail that matched their comfort level. Do we need to see explicit close-ups of throats being slit to know that Final Fantasy XVI’s Valisthea is a dark place? Near the end of the game’s demo, Clive’s mother finds him among the ruins. She’s always hated him because he didn’t manifest an Eikon, making him a useless heir, and when his younger brother Joshua was born with the power of the Eikon Phoenix, all her love and attention was turned his way. Her callousness reaches its peak when she finds Clive bloody and near-death in the aftermath of a climactic battle between Phoenix and the mysterious Eikon Ifrit. She tells her guards to kill him, but then, in a act of cold malice, tells them to sell him into slavery. This is a truly chilling moment in the narrative. We know that Anabella does not fuck around. But it’s undermined mere seconds later when she orders her two ladies-in-waiting killed. The soldiers slit their throats. Their only crime being in the wrong place at the wrong time as they witnessed Anabella’s callous treatment of her eldest son. My skin crawled as she ordered him into slavery, but the murder of two innocent, powerless women felt cheap, undermining of the intense familial betrayal that had happened mere seconds before.

Perhaps over the next 30 hours, Final Fantasy XVI will transform into a telling, incisive examination of the violence acted upon normal people at the whims and ambitions of the powerful. Maybe Benedikta and Hugo’s3 early-game dry humping symbolizes something profound about the way uniquely powerful people are drawn to each other through loneliness and isolation. Maybe sex and violence will be cleverly used to delineate the divide between 15 year old Clive’s youthful naivety and 28 year old Clive’s grizzled, weary adulthood. Several hours into the game, I’m doubtful.

The foundational story about nations warring over control of magical crystals, and the protagonist Clive sorting through the political and familial ramifications of his younger brother Joshua being blessed with the family magic (and, thus, being heir to the throne) is genuinely compelling and well told. Clive and Joshua struggle with their identity and the expectations (or lack thereof) thrown on them by fate without losing love for each other. Their father, the Archduke Elwin, is not a cartoon villain, but an empathetic father, a fierce leader, and a troubled husband. Thanks to a flash forward to start the game, we see how Clive loses everything yet still fights. As a magical malady called Blight spreads across the land, we see the human cost of uncontrolled magic as Clive explores ruined villages in search of goblins. We see how magic is controller by the noble class through the Eikon “dominants,” like Joshua, the dominant of Phoenix, and use this to maintain power and wage war. This is the good shit. This is Final Fantasy.

These emotionally driven conflicts, both personal and writ large, have been absent from many of the most recent Final Fantasy games, and feel far more mature than shots of gore-splattered children and nameless soldiers and ladies-in-waiting having their throats slit.

Final Fantasy XVI’s creative team has explicitly said they designed a fast-paced, single character action game as a means to attract a new audience—a stop gap to help recover after a decade of doldrums for the series. Game of Thrones debuted 12 years ago, and it’s been four years since the series’s famously disappointing final season. That’s a long time. Do the younger players that Square Enix is so desperate to court still care about Game of Thrones? Did they ever? Final Fantasy has always been a gateway series, it’s introduced millions of fans to role-playing games. Sex and violence will become a barrier to entry for many people, especially younger players, and directly stands in the way of the original generation of Final Fantasy fans—many of who have children now, that they’re introducing to their favourite series—from transferring their love of Final Fantasy to the next generation. The dramatic shift away from detailed RPG systems to a more combat-oriented combat system is pushing away many older fans. Building around a story specifically targeting the older generation that feels betrayed by these changes feels misguided at best, and actively harmful to the creator’s main goals at worst. It’s the fatal mistake of trying to be everything for everybody.

Game of Thrones wasn’t a hit because of its unprecedented amount of sex and gore—though that no doubt helped word of mouth—but because of the strength of Martin’s storytelling. Just look at what happened when HBO ran out of books to adapt and had to make up their own ending. My hope is that the rest of Final Fantasy XVI understands that compelling stories are built off emotional conflict and resolution. If the sex and violence can support that, like it sometimes did in Game of Thrones (but very often did not), then great, lets see what a no-holds-barred Rated M for Mature Final Fantasy can do. But if not, I worry it might be a missed opportunity to reach a generation of young fans growing up with parents who once loved the series.

Hidetaka Miyazaki recently worked with George R.R. Martin on 2022’s massive hit, Elden Ring—making it the “Game of Thrones of Dark Souls.” ↩

I’m enjoying the far gorier Diablo IV along with millions of other gamers right now, and grew up on violent gaming poster boy DOOM. ↩

Powerful “dominants” who control the Eikons Garuda and Titan, respectively, and act as principal protagonists early in the game. ↩

Member discussion