Astrolabe 35: Is 2023 the best year in video game history? Or the worst?

Fuck capitalism. Oh, and handheld gaming rules.

Spring of hope, winter of despair

Earlier this year, I started a playthrough of an excellent RPG on the Switch called Octopath Traveller II. I put it down partway through to start The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom, which I dropped halfway through to start Diablo IV, which I dropped partway through for Final Fantasy XVI, which I actually managed to complete (mostly due to a sense of obligation and self-flagellation) just in time for Sea of Stars, which I paused briefly for Super Mario Bros. Wonder, but still hope to complete in time for the Super Mario RPG remake in a couple of weeks. High end remakes of Metroid Prime, Ghost Trick, and Resident Evil 4 introduced a whole new audience to some all-time classic games earlier this year, but I couldn’t find time to fit them all in. Alan Wake II and Spider-Man 2 just dropped, and there’s still two months left in the year.

I still plan to go back and complete those other games, many of which I’ve put dozens of hours into already, but I haven’t even mentioned Baldur’s Gate III, Cyberpunk 2077: Phantom Liberty, or all the smaller titles like Cocoon, Dave The Diver, Viewfinder, Chants of Sennaar, Jusant, The Making of Karateka, Venba, Tchia, and on and on.

This is a long-winded way of saying 2023 has been absolutely stacked with incredible game releases, giving it a credible shot alongside 2004 (Halo 2, Half-Life 2, Metroid Prime 2, Metal Gear Solid 3, World of Warcraft, Minish Cap) and 1998 (Metal Gear Solid, Half-Life, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, Fallout 2, Resident Evil 2, Starcraft) at the title for the best year in gaming.

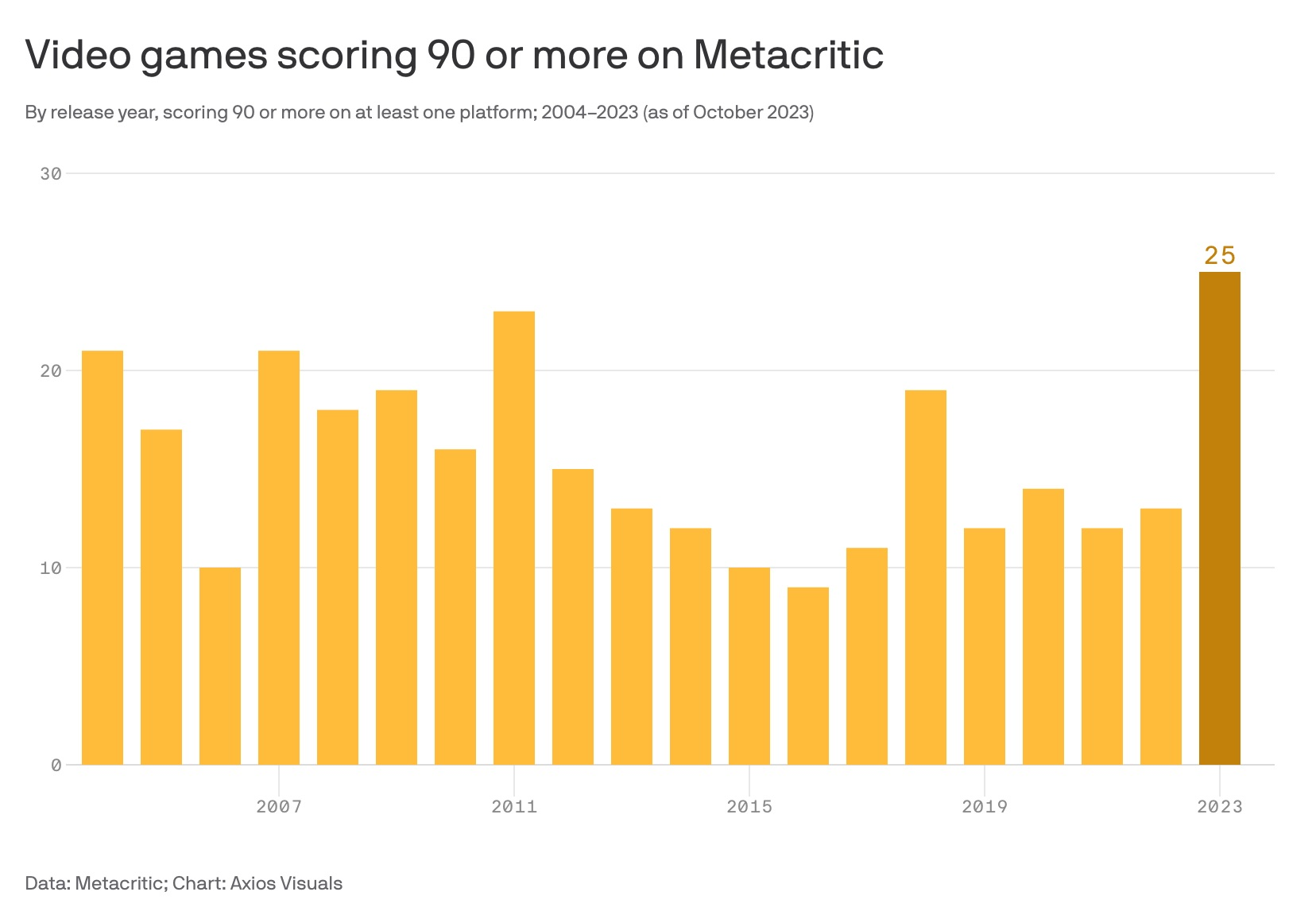

As reported by Stephen Totilo and Kavya Beheraj in Axios, 2023 “has the best-reviewed slate of video games of the last 20 years.” With 25 titles scoring 90 or higher on Metacritic, it’s edged out 2011 (Skyrim, Minecraft, Bastion, To the Moon, Deus Ex: Human Revolution, Dark Souls) by a couple of titles, and doubles up on nearly every other year since then.

It is, arguably, credibly, the greatest year in gaming. Ever.

Only, it’s actually one of the worst.

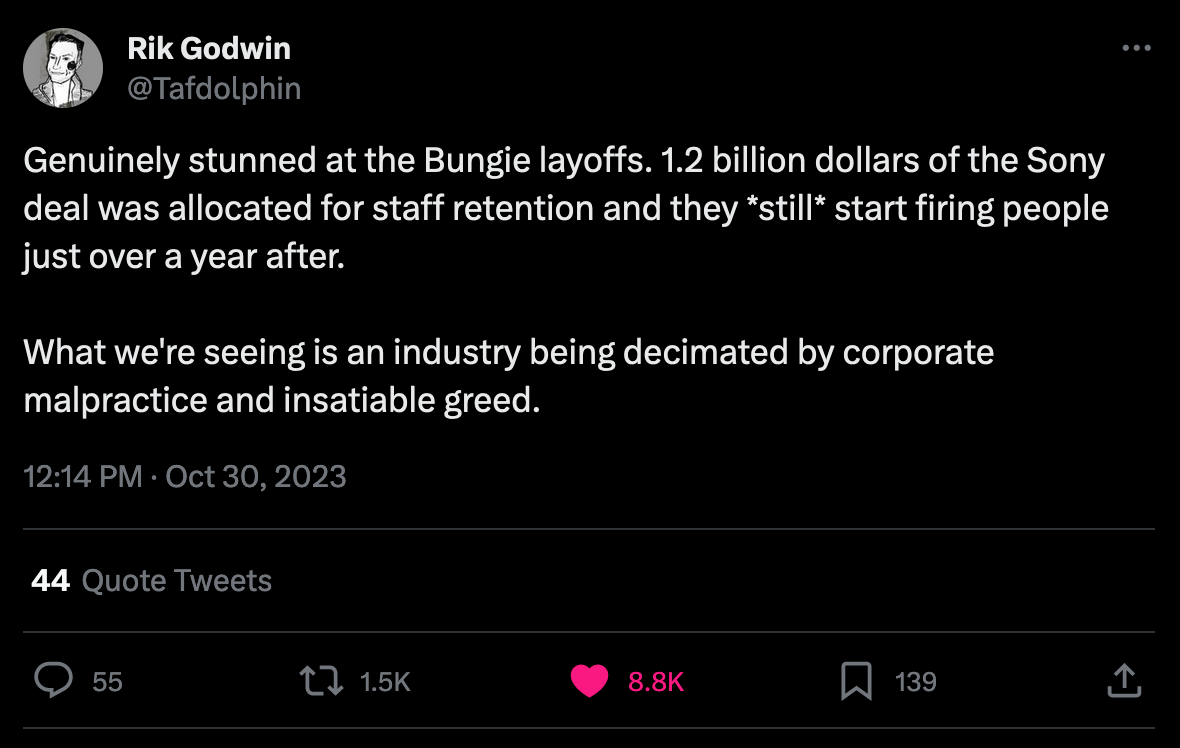

Alongside these brilliant games, 2023 has seen massive layoffs across the games industry—from developers to games media. Most recently, Bungie Studios laid off 8% of its staff (about 100 total people) in late October despite assurances from Sony (who acquired the Destiny 2 creator in early 2022) that layoffs would not occur. In fact, Rik Godwin relayed on Twitter that $1.2B of the $3.6B acquisition was earmarked for retention. These layoffs came directly from Bungie leadership, however, not Sony, neatly circumventing that little detail. The terms of the layoffs, reported by Forbes’s Paul Tassi, which include as little as one day of extended benefits for laid off employees, are a grim reminder of how little corporations care for the humanity of the people who drive their business and profits.

This is just the latest in a long line of layoffs at developers like Media Molecule, Epic Games, Volition, Bioware, and more. Adding the Bungie layoffs to the public data collated by Farhan Noor at videogamelayoffs.com, at least 6,500 people have been laid off this year.

This doesn’t even begin to touch on the scorched earth layoffs occuring in games media over the past year. Since mid-2022, we’ve seen closures or extreme staff reductions at sites like the Washington Post’s Launcher (closed), Fanbyte (significantly reduced), Input (closed), Inverse (layoffs), Waypoint (closed), and many others. I’ve gone from being able to reliably land freelance pitches, to rarely even getting responses.

“Redundancies are not uncommon, but the pace at which it's happening in games media is swelling,” said Khee Hoon Chan in a GamesIndustry.biz piece called “Why do games media layoffs keep happening?”

“If you have been following the headlines, you may conclude that no one is reading very much these days. After all, layoffs in games media have been taking place with alarming frequency, with businesses often citing ‘structure change’, ‘supply-chain issues’ and ‘very tough market environment’,” Chan wrote. “Layoffs are now endemic to the games media landscape and the broader journalism field, with many affected sites held together by a skeleton crew or operating with a masthead of newer writers.”

These closures and layoffs have a trickle down effect, pushing freelancers already fighting for scraps lower down the ladder as they’re pitted against an increasingly larger pool of experienced and connected writers with a dwindling prize pool of freelance budget. It means fewer voices, less opportunity for marginalized writers to bring forward unique stories, and many writers being edged out of the industry altogether.

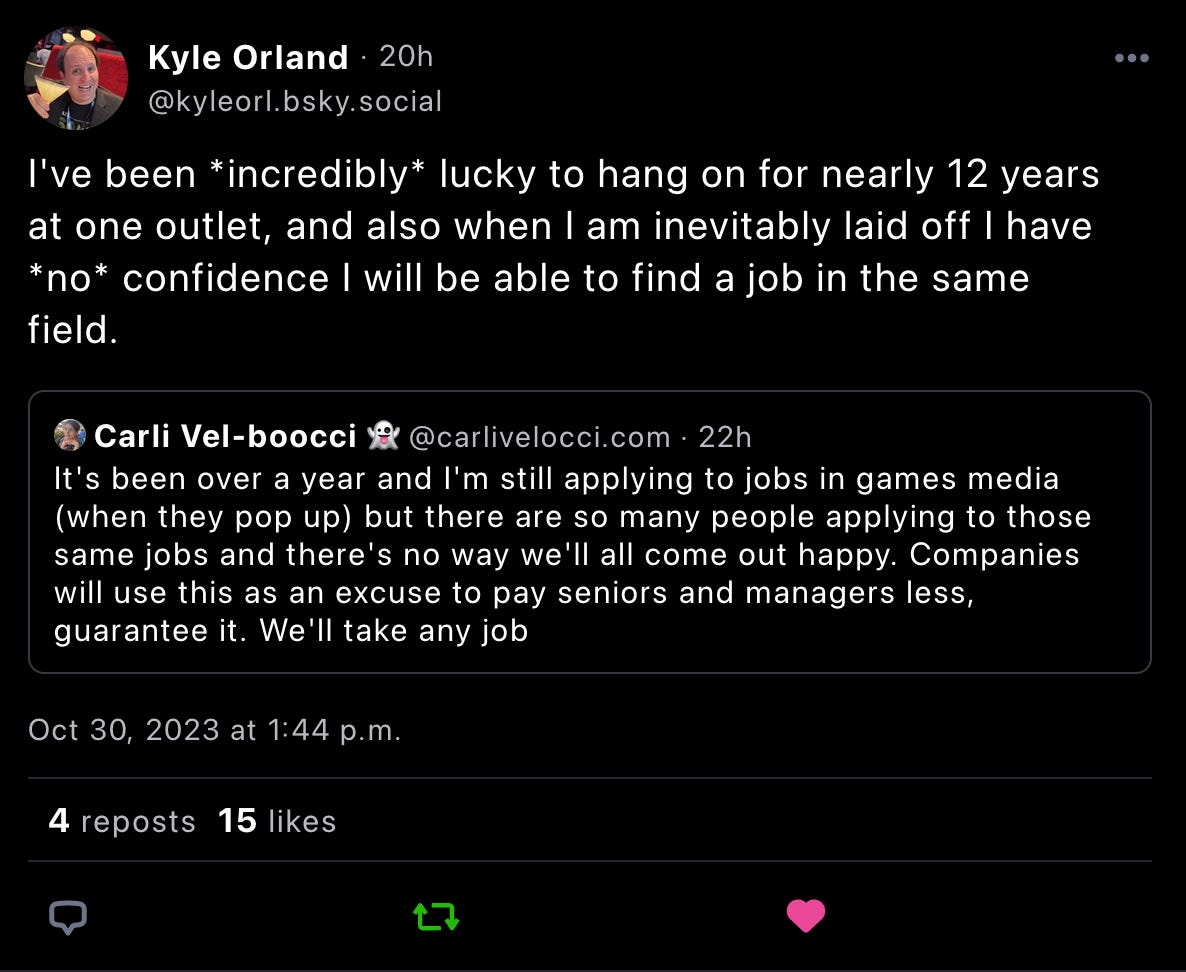

Veteran games journalist Kyle Orland recently expressed doubts on his ability to transition into a new full-time journalism job if he were laid off from his current role as Senior Gaming Editor at Ars Technica, a position he’s held for over a decade. Copyeditor Carli Velocci has experience at many high profile video game publications, but she’s been searching for fulltime, permanent work for over a year. If writers of Orland and Velocci’s ilk and experience can’t make it, what hope does anyone have? And what does that mean for the future of games media? If it can’t maintain a healthy, independent press that’s able to pursue stories without worrying about corporate profitability, and instead becomes even more reliant on the messaging crafted by increasingly tight-fisted gaming PR departments, games media will become little more than a glorified press release platform.

Video games have never been better, but video game journalism is dying, and the people who are most passionate about making video games, and covering video games in the media, are burning out. This grim juxtaposition exposes the uncomfortable cost of 2023’s banner year of video games: It’s unsustainable, no matter how good the games are.

Layoffs are a failure of leadership. Full stop. CEOs should, at the very least, be required to take pay cuts equal to the percentage of employees laid off. Layoffs by profitable companies should be illegal. There needs to be accountability for leadership failing to put people before profits. Instead they just fail upwards, every time, until they land multi-million dollar buyouts and juicy retirements. That layoffs keep happening with little-to-no repercussions for the people in charge leads to a few potential conclusions: a) intentional malpractice and greed in the name of shareholder profits, as suggested by Godwin in his tweet above, b) it results from complete lack of accountability for leadership making bad business decisions, c) it’s an industry with capitalist goals at the top, but artistic needs on the ground level, or, realistically, d) all of the above.

As pointed out by Bertine van Hövell, data indicates that these layoffs are counterproductive even from a capitalist perspective. Van Hövell highlights this piece in the Harvard Business Review:

The findings of two decades of profitability studies are equivocal: The majority of firms that conduct layoffs do not see improved profitability, whether measured by return on assets, return on equity, or return on sales. Layoffs are especially hard on the performance of companies with a high reliance on R&D, low capital intensity, and high growth. Market response to layoffs was also less positive than might be expected, with three-day share prices of firms conducting layoffs generally neutral. Higher valuations were given for layoffs perceived as helping firms in financial distress return to profitability as well as those that were strategic and forward-looking. Layoffs undertaken only for the purpose of reducing costs tended to lead to drops in share price.

With that in mind, it cannot be ignored that these binge layoffs are happening at a time when the games industry is rapidly opening up to unionization. In January, 2023, Polygon’s Nicole Carpenter joined NPR’s Juana Summers to discuss the rise of unionization in the games industry, and the larger impact it was having in the tech sector.

“A lot of workers that I've spoke to have pointed to the wider union wave as inspiration,” explained Carpenter. “Workers across the United States deserve a union to be able to have a say in their workplace and how they're treated there. And that's no different with video game workers than it is anywhere else.”

Unionization spooks corporations and shareholders, it empowers employees, and shifts the balance of negotiation and profitability away from the suits toward the people who actually do the work. Layoffs like we’ve seen in the games industry are specifically and intentionally designed as a haymaker to keep remaining employees in line, balanced on a knife’s edge as they kill themselves to create and write about video games. When you’re always a day away from being laid off, the risks of joining unionization efforts can feel insurmountable.

There’s a glimmer of hope, however. Baldur’s Gate III, Super Mario Bros. Wonder, and Tears of the Kingdom are some of the highest rated games of the year, and are all likely to end up on multiple Games of the Year lists. They were also, unlike, many big budget AAA games, made by development teams given free reign to experiment and work on the game without a hard deadline.

Conversely, Final Fantasy VII Rebirth director, Naoki Hamaguchi, spoke with Bloomberg’s Jason Schreier about how his team was able to produce such an impressive and large game in just a few years. “In an era when many video games take six years or longer to make, many players have wondered how the developers at Square Enix were able to finish Final Fantasy VII Rebirth in less than four years,” Schreier wrote.

“The secret, Hamaguchi said, was a trait that many other video-game studios don’t seem to prioritize: team chemistry. Between 80% and 90% of the Final Fantasy VII Remake development team stuck around to make Final Fantasy VII Rebirth, which allowed for more efficient development, even during the height of the pandemic.”

Both these approaches prioritize a development environment that decouples the creators from the pain points of capitalist-driven quarterly profits. By empowering employees, Square Enix, Larian Studios, and Nintendo were able to create an environments that supported the developers’s needs—whether that was Tears of the Kingdom and Wonder’s long, secretive development periods focused on experimentation and perfection, Baldur’s Gate III’s extended public beta, or the chemistry and experience of Final Fantasy VII Remake’s team sticking around for Rebirth.

These cases paint a hopeful future for a games industry that values its people as more than labour statistics and numbers in a P/L report. However, capitalism requires an underclass to create profit at the expense of their own livelihood, and until we see an industry—and a game-buying public—willing to push against the current obsession with profit before people, this vicious cycle of layoffs, rehiring at a lower salary, and laying off again, will continue.

I don’t have the answers, though I know that anything CEOs abhor as much as they abhor unionization must be good for the laymen, and it remains a vital tool for the survival of the games industry. I do wonder if we start to see new forms of collective bargaining and employee empowerment over the next decade. Perhaps instead of going at it alone, we see smaller groups of game developers, writers, programmers, artists, etc. form their own small employee-owned companies that contract out their services as a team to larger developers and publishers. Perhaps you have a team that specializes in level design for action games, a crack team of pixel artist and animators, or a lighting team that’s worked together across several games and knows the ins-and-outs of raytracing, baked lighting, and HDR implementation. Rather than go at it alone, and face the heavy hand of layoffs as individuals, these agile and experienced teams would benefit from sticking together, and letting their expertise and chemistry replace the endless onboarding, training, and team integration resulting from regular layoff/hiring practices.

At the end of the day, no matter how good the games are, if the industry is designed in way in which it can produce $200B in revenue each year, yet still somehow create an environment where the people making the games do so with a guillotine hanging over their desks at all times, there needs to be reform. We need gaming to decouple itself from capitalist profit structures and transient employability, and recentre itself on quality-of-life and job security. Because if we can’t take care of the people making them, it doesn’t matter how good the video games are in the end.

Out & About

Out & About is where I highlight my work around the web—some recent and some old favourites.

Why sit at work wasting company time doomscrolling on Twitter when you could be playing these fabulous retro (and retro-inspired) games right in your browser window, instead? Over on Lifehacker, I’ve got a run down of nine browser games that’re sure to leave you nostalgia, satisfied, or some combination of the two.

When I was a kid way back in the ‘80s, vintage video games were new. Stuff like Super Mario Bros., Tetris on the Game Boy, and Final Fantasy III had pixel art and chiptunes, but they weren’t yet retro games; we just called them video games.

What we didn’t have was access to the internet, and an endless pool of talented game designers releasing fun, cute, and genuinely well-designed games for free on platforms like Itch.io that you can play right in your web browser.

With platforms and tools like Unity, PICO-8, and GB Studio, it’s never been easier for people to make their own games, and so many of these tools specifically push designers towards the classic look, feel, and gameplay of the ‘80s and early ‘90s. With that in mind, I’ve gathered together some of my favorite browser-compatible games with major vintage vibes (and thrown a couple of stone cold classics in the mix too).

Read “You Can Play These Retro Games in Your Browser” on Lifehacker

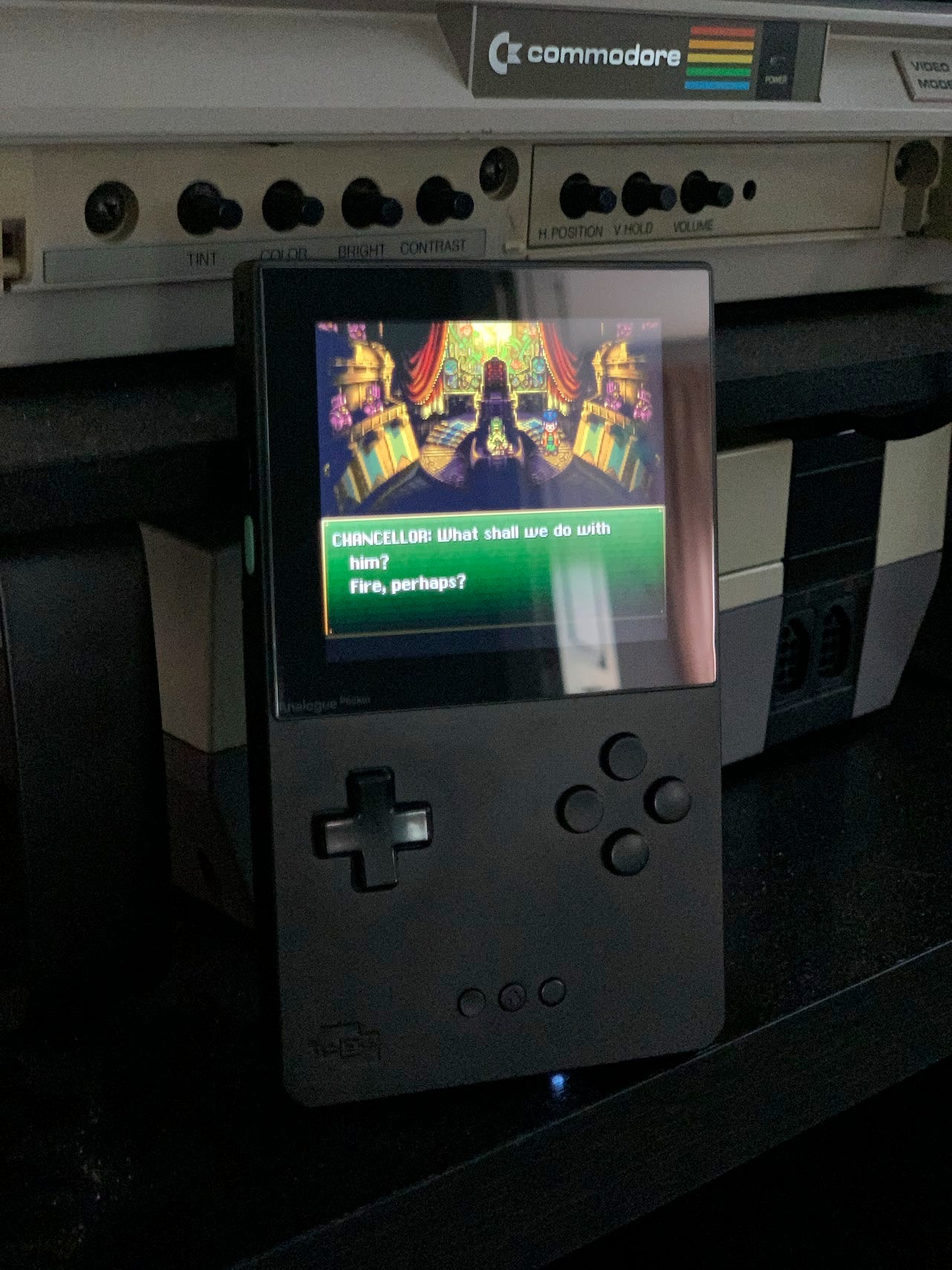

LTTP—Analogue Pocket (2021, Analogue)

LTTP (Late to the Party) is a regular column where I let Twitter decide which retro game I’ll play for an hour. Do your worst, Twitter!

Y’all, as a lifelong handheld gaming enthusiast, I have been waiting, and waiting, and waiting to finall get my hands on an Analogue Pocket, and, after 18 months (seriously, a year-and-a-half) of refreshing my order status page, I finally got the unit I ordered in early 2022 (as a nice reward for turning in the first draft of my book, Fight, Magic, Items). First released in 2021, this FPGA-powered handheld device can play original Game Boy, Game Boy Color, and Game Boy Advance carts (along with Game Gear and a few other consoles, with cartridge adapters) as well as ROM files for many other consoles—handheld and not—via a digital platform called openFPGA1.

So, if you’re like me and have a huge collection of original carts, or you’ve got a digital-only collection, there’s an impressive amount of versatility in the Pocket, and it opens up a huge amount of gaming history at a relatively low price-of-entry.

(Except you can never buy the thing due to low availability. Anyway. Onward.)

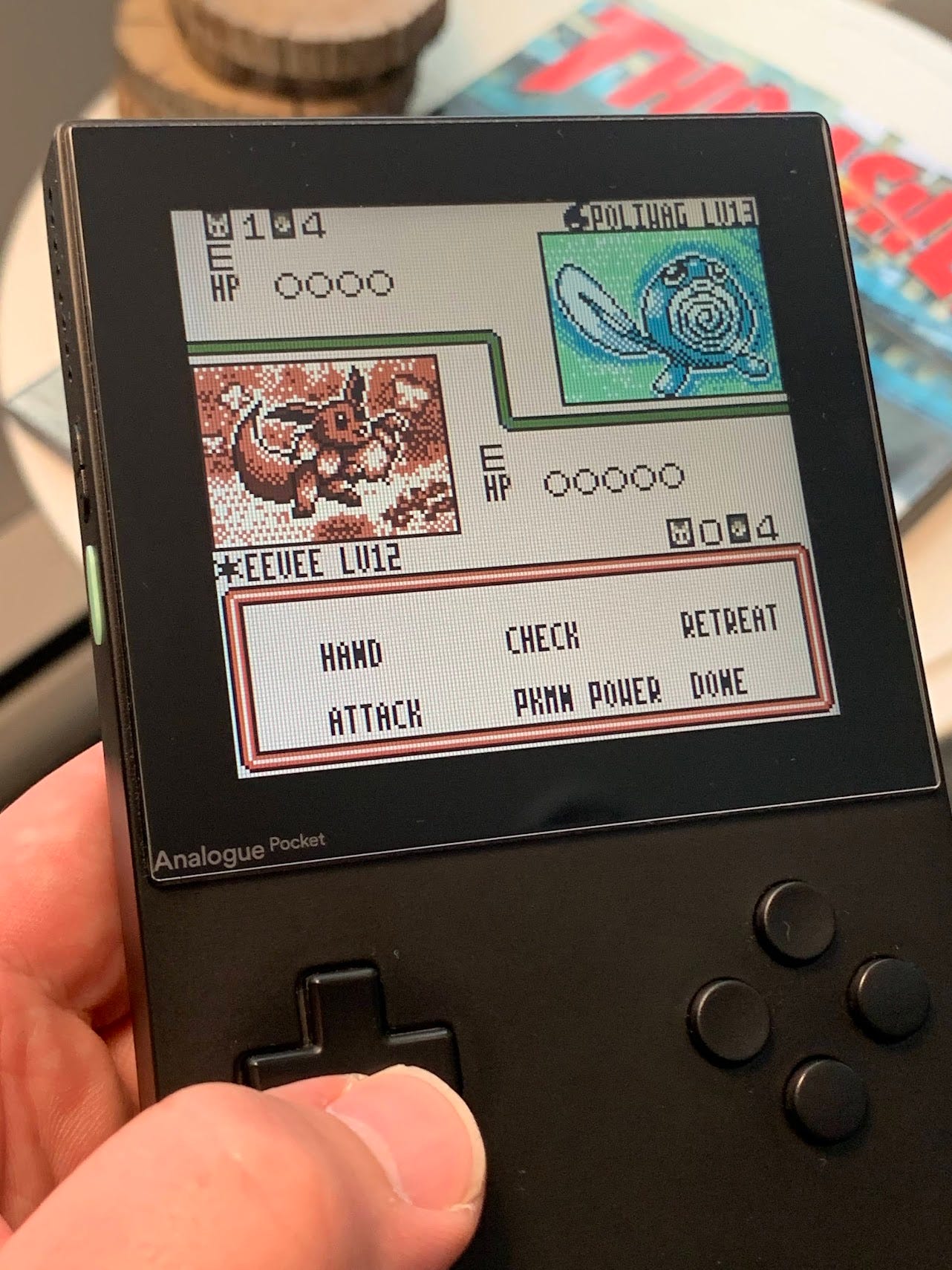

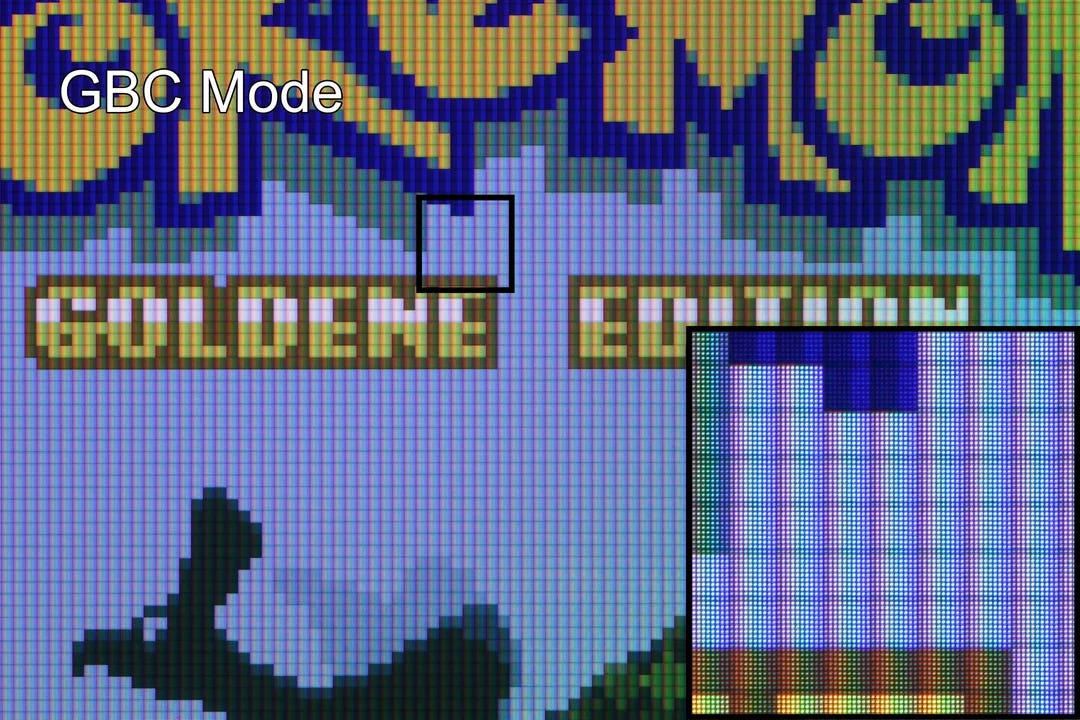

The first thing any review of the Analogue Pocket mentions is the screen, and for good reason. Clocking in at exactly 10x the resolution of the original Game Boy, games scale perfectly, without any sort of shimmer, and absolutely pop off the screen thanks to its impressive brightness, colour depth, and the system’s built-in screen filters designed to emulate various old consoles.

Most impressively, the Analogue Pocket uses the screen’s high DPI to emulate older LCD technlogy by breaking each on-screen pixel down into its requisite RGB sub-pixels (for the Game Boy Advance, in this instance), leading to an impressive fidelity unlike anything I’ve seen on similar handheld devices. Look closely at the cut out in the screenshot below, nad you can see how each square pixel is made up of vertical coloured bars of varying brightness.

The rest of the playing experience is equally satisfying. The device itself its weightly and comfortable (though, admittedly, I have smallish hands, and people with larger hands often complain that it’s a bit cramped). Having the four face buttons lends nicely to support for other consoles like the SNES, but the Pocket’s OS is loaded with options that let you reassign buttons, and customize many aspects of the experience to your liking.

The OS itself, dubbed Analogue OS, has received a lot of great feature upgrades since the Pocket’s initial release, most notably Library, which is a reference quality games database accessible for all of the cartridges you’ve played on the device. That coupled with lots of screen options, save states for all supported carts (and a few OpenFPGA cores), and screenshots makes it a great device for picking up and play sessions, capturing screenshots, and playing various Rom hacks. A true all-in-one experience.

The real elephant in the room is OpenFPGA. Playing all my original carts is great, and I’ve already managed to play through a couple of Zeldas, Metroid: Zero Mission, and Pokemon Trading Card Game, but having access to pretty much every pre-Nintendo 64/PlayStation era console on a handheld gaming device that can produce nearly perfect hardware emulation is almost overwhelming with its options. Couple this with the Pocket’s official HDMI dock, which outputs to your living room TV at 1080p (and eventually, with an upcoming 2.0 update, to your CRT at native resolution via Analogue’s DAC device), and you’ve basically got a full-featured retro gaming device that covers over two decades worth of games.

18 months was a long time to wait, frustratingly so at times, and the overall cost of shipping it to Canada, when factoring in shipping costs, currency conversion, and duty, was not easy to stomach, but, honestly, it was worth every penny.

Now, back to Holodrum, I go!

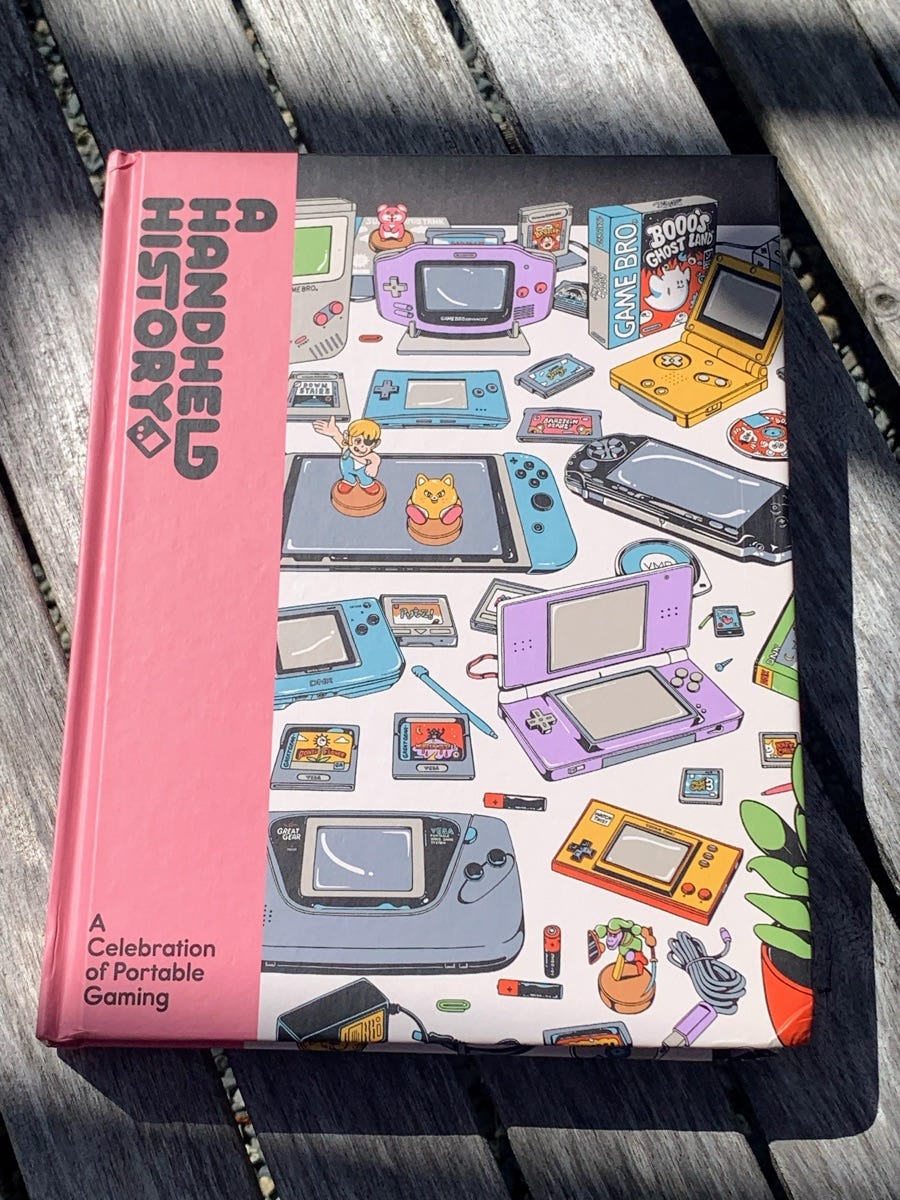

Recommended Reads—A Handheld History by Lost in Cult

Since debuting just a few years ago, UK prestige press Lost in Cult has impressed with its content-packed [lock-on] series (which, full disclosure, I’m contributing to in its sixth volume), and history-focused books like A Handheld History. From the early days of the Game & Watch, through the heights of the Game Boy and beyond, A Handheld History examines the important role portable gaming has played on the industry’s impact around the world. Accompanied by gorgeous illustrations and photographs, and jammed full of great content, it’s a wonderful book to sink into for an evening or page through slowly over the course of months. A mainstay on my night side table, A Handheld History is a love letter to gaming history, and a book I return to time and time again.

A Handheld History is available now from Lost in Cult. Quest Markers

Quest Markers is a collection of the coolest stuff I’ve read around the web lately.- The Dungeons & Dragons Players of Death Row (New York Times)

- The Strange Story Behind ‘Baldur’s Gate 3,’ One of the Year’s Biggest Releases (Bloomberg)

- 'Game Boy Mom' photo traced to Sask. after more than a decade of memes (CBC)

- The fandomization of news (The Verge)

- Yelling is not journalism (Insert Credit)

- Life and Death in Final Fantasy VII (Tor.com)

- Tchia and a single breath of the wild (Backlog)

- Critical Role Lays Out the Next Era in Tabletop Games and Live-Action Role-Play (WIRED)

- 'That's what makes the fantasy world feel tangible': Fonda Lee discusses her novella Untethered Sky (CBC)

- The Secret Behind the Success of ‘Baldur’s Gate 3’ (Bloomberg)

- Trails into Reverie Continues the Most Ambitious Epic in Games (Paste)

- Final Fantasy XVI: The one that can say “fuck” (Medium)

- “What Does It Mean to Be in Love With Somebody and Disagree With Their Choices?” — The Creators of The Dragon Prince on Season Five (Tor.com)

- Indie game Venba serves up Tamil cuisine and family's heartfelt story of life in Canada (CBC)

- "They need us. We don't need them:" The fall of Twitter is making the trolls and grifters desperate (Salon)

- Xenoblade Chronicles Tells Stories for Our Times (Paste)

- An Ode to the World’s Most Average Dinosaurs (Smithsonian)

- The Case for Spoilers: Why Some People Are Happier Knowing How the Story Ends (Washington Post)

- 'A Plague on the Industry': Book Publishing's Broken Blurb System (Esquire)

- Can the Harry Potter fandom carry on while ignoring J.K. Rowling? (Polygon)

- In A Year Of Big Games, Sea Of Stars Is Refreshingly Small (Kotaku)

- Why Doom creator John Romero says video games are 'the greatest art form' (CBC)

- Raising The Reservation Dogs (Romper)

End Step

✊✊✊

Support

There are lots of ways to support Astrolabe and my other work. Check ‘em out!

Keep In Touch

Enjoy Astrolabe? Want more SFF and retro gaming goodies? You can find me on Twitter and my website.

Credits

Astrolabe banner photo by Shot by Cerqueira on Unsplash

“Aidan, you keep saying this word and I don’t know what it means.” FPGA stands for Field Programmable Gate Array, and it’s basically a blank chip that can be programmed to replicate the sturcutre/behaviour of other hardware. So, where something like BSNES on your computer emulates the software, FPGA emulates the hardware, allowing the game software to run natively. It’s a fine distinction on the surface, and probably doesn’t matter to most people, but under the hood, it’s a world of difference. ↩

Member discussion