I'm loving Tunic—and it's all thanks to "No Fail" mode

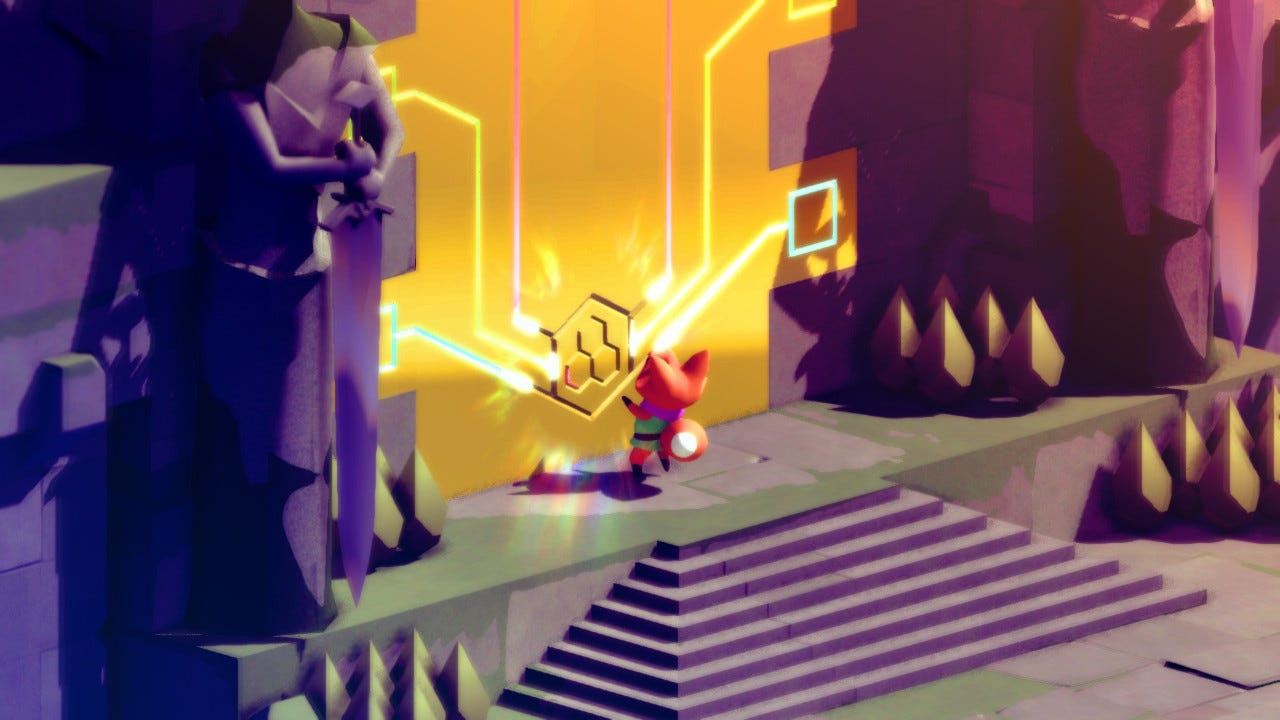

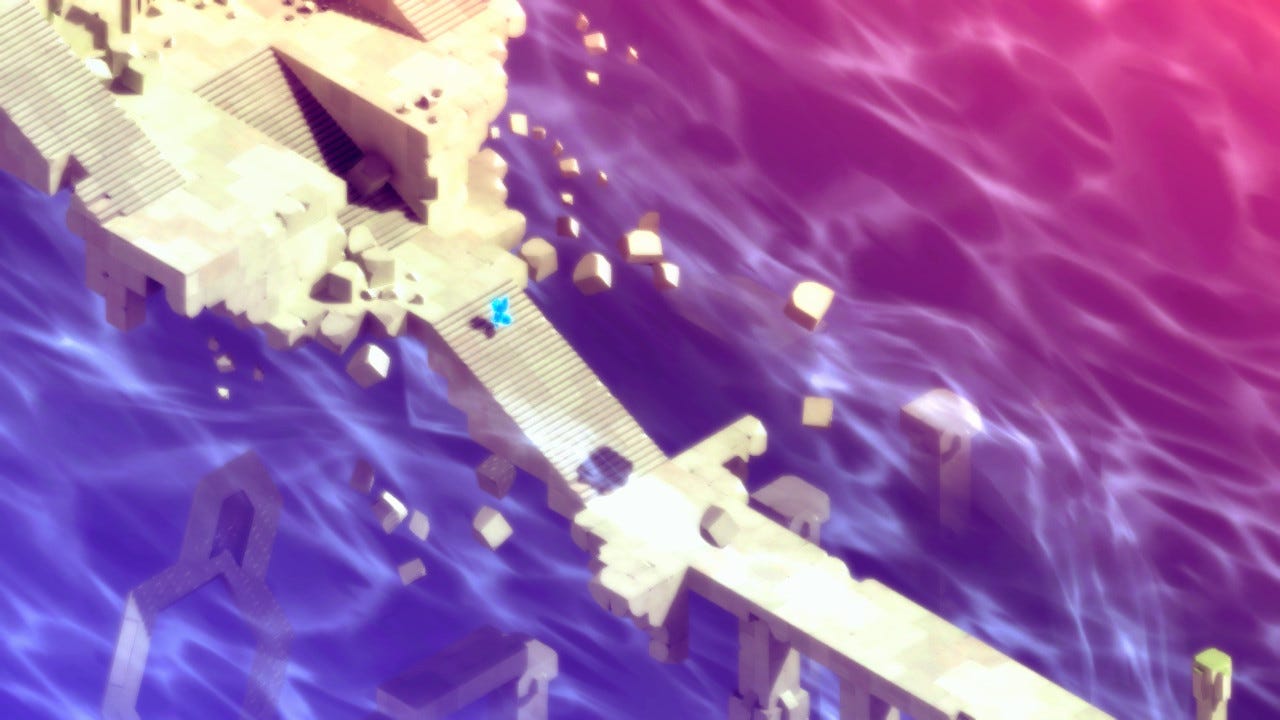

During Tunic’s opening moments, you’d be forgiven if you thought it was a simple Zelda clone. Its protagonist—an adorable fox bearing a striking resemblance to The Legend of Zelda’s hero Link—wakes on a lapping shore, bringing to mind Zelda’s classic Game Boy outing, Link’s Awakening. As you venture forth, a familiar island reveals itself—complete with sandy beaches, choppable bushes, derelict buildings of a long lost population, waterfalls hiding secrets behind their misty spray, mountains to climb, caves to plumb, and everything else you’d come to expect from a wild, once vibrantly populated island.

But, then.

Behind a towering set of gleaming golden doors in an otherwise innocuous landscape, you’re taken to a ghostly realm, revealing new depth to Tunic’s mysteries. This ain’t an ordinary island. Later, you enter a windmill, its rotor blades still turning despite no caretakers in sight, and through a backdoor you enter into a realm of nothingness, populated only by a giant, demonic shopkeeper who silently sells you a potion upgrade and some firecrackers.

Tunic begs to be explored. There’s something new, challenging, unique, and beautiful around every turn—a delight revealed for ever moment you spend playing. It’s bursting with questions, but serves up few plain answers. In this way, Tunic has far more in common with the original The Legend of Zelda on NES than Link’s Awakening or newer titles like Breath of the Wild. Zelda has always utilized exploration and puzzle solving at its core, but not since the original has its world offered such unfettered, unguided, unabashed emphasis on exploration as Tunic.

With so many modern games focusing on reducing friction,1 players are often hand-fed experiences that previously required active problem solving. As a recent example, God of War Ragnarök has been criticized for how quickly its NPCs pipe up to solve puzzles if it seems like the player is struggling. See Mark Brown’s recent video on Game Maker’s Toolkit that examines the issue, and contextualizes it within larger game design trends:

Titles like Tunic and Elden Ring, on the other hand, push in the opposite direction by letting players loose in a large world, and encouraging them to explore through the use of environmental design, interesting landmarks, environmental diversity, and an understanding that it’s okay—good, even—if players experiences the world in their own way and at their own pace. It’s even okay, in fact, for players to miss content during their playthrough. That’s part of the unique opportunity video games have to give players an active role in the story—something that’s impossible with novels, movies, etc.2

Tunic wants you to pay attention, use your intuition, take notes, consult its handdrawn, non-interactive map, and sink into a world bursting with history, lore, and narrative. There’s no dialogue in Tunic, and the only written content in the game world is conveyed through an unreadable script that becomes slowly, sparingly decipherable by the player over their playthrough. Its exemplary visual and interactive storytelling that succeeds far better than many games loaded with written content.

But, while Tunic successfully adopts this mode of storytelling from Hidetaka Miyazaki’s Dark Souls and Elden Ring—which themselves drew inspiration from the original The Legend of Zelda in the way they centre the player in the narrative—its co-opting of those games’s studious and punishing combat is less favourable. Especially at the start of the game, your fox's range is short and they deal poor damage, mobility is limited, enemies have small windows of vulnerabiltiy, and you've few tools at your disposal. It's difficult, but lacks complexity, which is a poor and frustrating combination. For a game so focused on exploration, you’ll die a lot3.

Miyazaki’s games succeed here because they give equal weight to combat and exploration. They’re inextricable from one another and give the player a plethora of options for how they build their character. This, in itself, makes combat and developing your playstyle part of the game’s narrative. Elden Ring offers a harsh world, full of awful people, dangerous magic, and menacing enemies. It’s a world where you expect to feel pain. Each death feels like the cost of learning something new.

Tunic looks like a Saturday morning cartoon, putting it at odds with the difficulty of the combat, and exacerbating the frustration of dying and having to retrieve your corpse to ensure you don’t lose resources.4 It’s not a world where mastery of combat fits the tone. Instead, combat stands in direct opposition to the game’s most engaging elements. It turned off a lot of players at launch who were otherwise enjoying the game, and several people reached out to me when I said I was playing Tunic to say they liked the idea of playing Tunic more than they actually enjoyed playing it.

It was, in the end, a misguided mismatch between consequence and desire.

As I’ve written about previously, it’s not that I don’t have the chops or experience to push through difficult games. I platinumed Elden Ring earlier this year and have written about the ways Miyazaki’s approach to design has changed to be more inclusive of players along all spectrums of skill, experience, and taste. I contrasted this against Nintendo’s Metroid Dread, which had very similar issues to Tunic when it first released: the exploration was incredible, but it was hampered by ridiculous difficulty spikes, especially with bosses. Nintendo wisely patched in a “rookie” mode that allowed many people to finish a game they’d previously dropped in frustration.

And, wouldn’t you know it, Tunic did something very similar: they released a reduced combat difficulty option to take the edge off for players who weren’t having fun. Add this to the game’s “No Fail” mode, along with a few other nice accessibility options, and, and Tunic (recently released on Switch and PlayStation 4/5) finally feels like a game succeeds on its strengths, rather than one dragged down by its flaws.

When starting Tunic, I chose the easier combat option, but didn’t toggle on “No Fail” mode or the option for unlimited stamina. This has presented a fair bit of challenge, in line with the cognitive challenges associated with exploring the world and dissecting the game’s integral, fascinating, and highly detailed internal game manual5. And, when the going gets really tough, like against the challenging bosses, or when I'm up against the ropes and don't want to retrace my steps through a dungeon post-death, I'll pop on "No Fail" mode for a beat until I reach safety. This is the type of opt-in accessibility that I praise in the Astrolabe issue I liked to earlier. It saves me the type of frustration I don't want to experience in a game that's otherwise so delightful, but can also be toggled off when I don't need it.

While I respect and understand the value of artistic intent, video games are a medium where the balance of player needs across different spectrums must be understood and designed around. Needlessly difficult games without options to tweak player experiences are inherently inaccessible and inequitable. Constraints on a players time or goals, physical or mental disabilities, experience, and many other factors contribute to the reasons why a player might not be able to persevere through difficult games,6 but they're no less deserving of the full experience. I respect that Tunic conveys a world that requires the player’s undivided attention, but I also appreciate that its creators recognized these barriers could also present players from drawing full enjoyment from the experience.

“No Fail” mode offers me an experience in Tunic that’s exactly to my tastes. It allows me to focus on exploration—a truly open world environment where I don’t feel gated off by difficulty, only whether I’ve found the traversal tools necessary to proceed. I can linger on its mysterious lore and gorgeous world at a pace and in a manner that suits my tastes. It provides access to a hostile world for all manner of players, without gating off the original intended experience for those who prefer to tough it out.

Back when The Legend of Zelda debuted in 1986, it offered an unprecedented opportunity to explore a fantasy world on home gaming consoles. It didn’t hold the player’s hand or give them a tour guide through the journey.7 It didn't lore dump or explain its story. Getting lost, ekeing out secrets, taking down dungeons one at a time—that was its story. Tunic recaptures that spirit with nuance and charm, and, thanks to “no fail” mode and a bevy of other accessibility features, it’s a journey that welcomes a broad range of adventurers to its mysteries. It’s a Zelda clone, sure, but far from a simple one.

Tunic is available for the Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 4/5, Xbox One, Xbox Series X/S, Windows, and macOS.End Step

While flagship Astrolabe issues will always be free, I’m looking to expand my offering for paid subscribers, so you’ll be seeing more one-off features like this from time-to-time. I hope you enjoy it, and thanks for supporting Astrolabe!

Support

There are lots of ways to support Astrolabe and my other work. Check ‘em out!

Keep In Touch

Enjoy Astrolabe? Want more SFF and retro gaming goodies? You can find me on Twitter and my website.

Credits

Astrolabe banner photo by Shot by Cerqueira on Unsplash

Basically, any moment that might make the player quit playing the game. These might include: making sure they don’t get stuck on a puzzle, clearly signposting the critical path, highly detailed maps littered with icons tracking everything in the game, etc. ↩

With the exception of Choose Your Own Adventure books or those interactive Netflix films, I guess? But even that’s still a prescribed set of branching paths, rather than true freedom. ↩

Or maybe not. But, more on that in a moment. ↩

Another element lifted directly from Miyazaki’s Souls games. ↩

It’s seriously a marvel. Based on old NES and Super NES manuals, there’re 50+ pages that the player can discover throughout the world, and each page reveals something new about the adventure—whether that’s the purpose of various items, a dungeon map, or even puzzle solutions scrawled out in ball point pen. It’s such a brilliant, fun addition to the game. ↩

Git gud, son. ↩

"Hello!" "Hey!" "Listen!" ↩

Member discussion