Hayao Miyazaki’s Lost Magic of Parenthood

How the legendary Studio Ghibli filmmaker explores the intersections of childhood, parenthood, and magic in his most famous films.

One of life’s great joys is watching your children play. Through a kitchen window overlooking your backyard, at the beach, exploring a park. There’s great pleasure in observing the unobserved. You see their joy, watch them solve problems, navigate complex social situations, work together, fight, hug, laugh, run. Be free. You become lost in their imagination and for a fleeting moment recapture the wonder of a long-ago childhood. Watching your children play is an opportunity to see the world through excited eyes.

It’s this warm, emotive sense of simplicity and well-being — as though, somewhere deep within your heart, life’s purpose becomes something you can finally grasp. It’s fleeting — like a soot sprite captured between clapped hands, gone the moment you try to examine it, smudged palms the only trace of its existence.

As I struggle to articulate these feelings in a way that doesn’t feel contrived or artificial, the cinematic works of famed Japanese filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki call from the back of my mind. Particularly loud are his triumvirate examining these themes with ageless, crystalline clarity: My Neighbour Totoro, Spirited Away, and Ponyo.

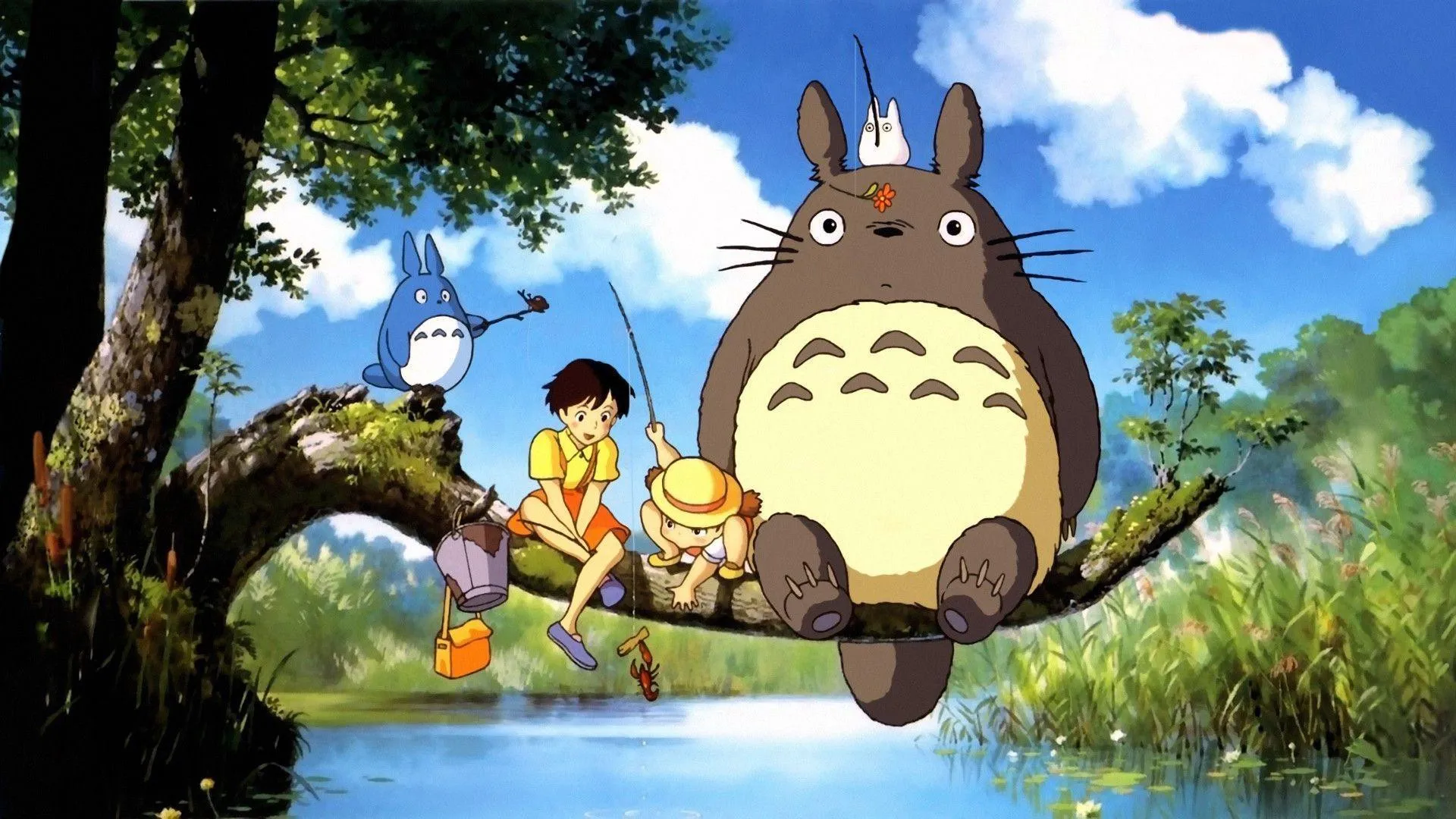

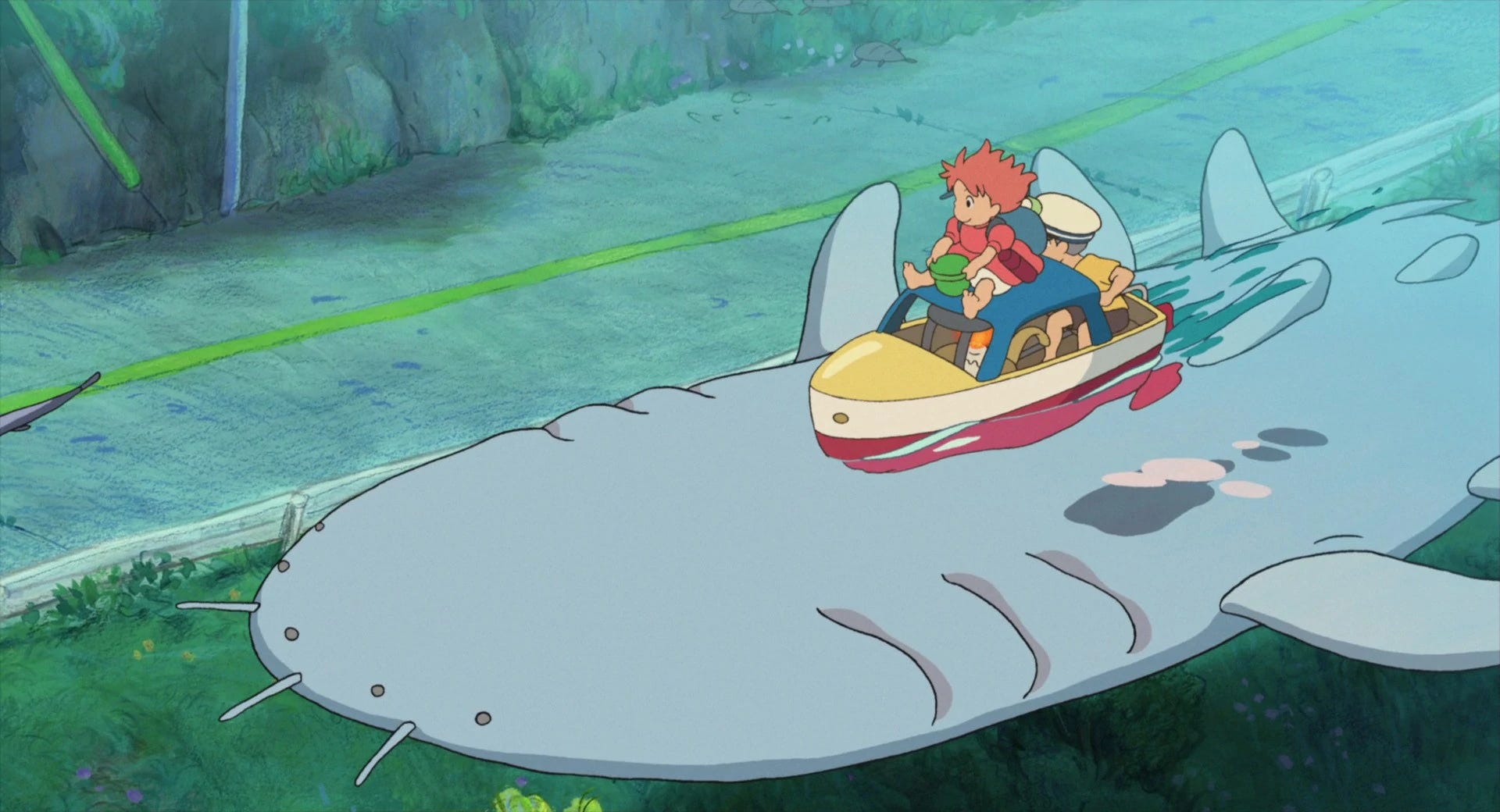

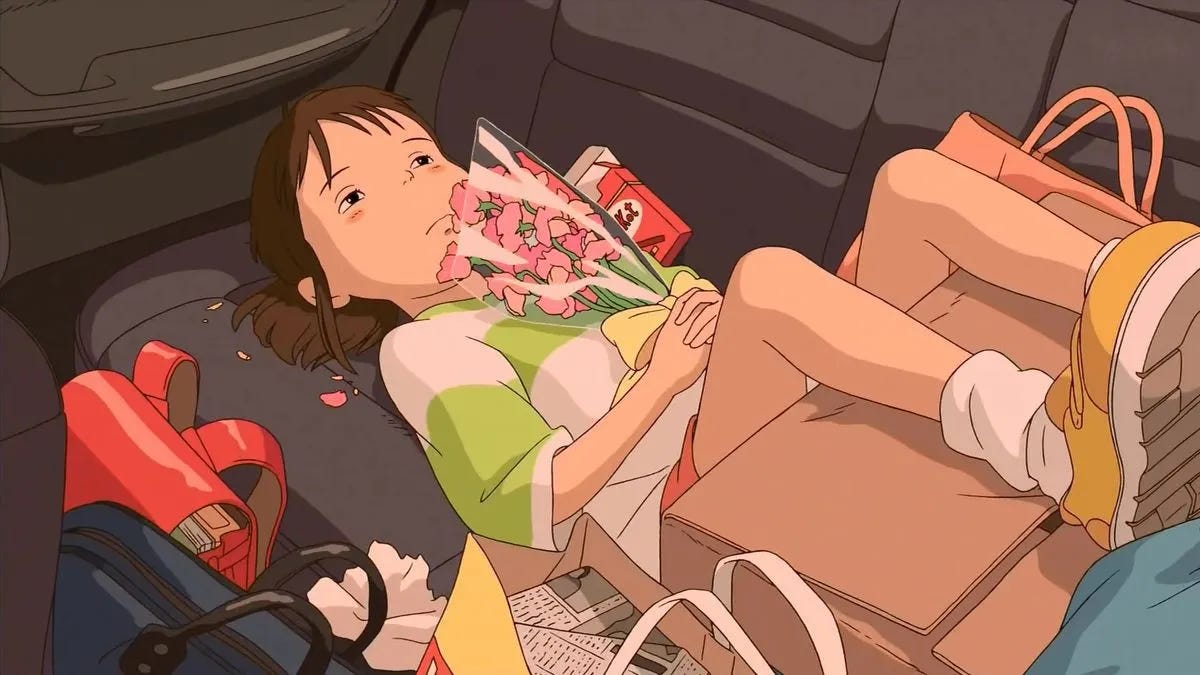

The beating heart of these films are the children around whom the story warps, and the interactions they have with the magical and natural worlds around them. A small boy named Sosuke meets a magical goldfish; Chihiro explores a bathhouse home to myriad spirits; sisters Satsuki and Mei befriend a lovable troll called Totoro. Miyazaki is well loved for his evocative recreations of rural and urban Japan throughout the 20th century, but the magical additions are what make them classics.

Central to these films is the way their magical worlds are revealed to their young protagonists, leaving the parents — obsessed with the things that haunt all adults — unaware of the wonder under their very noses. Miyazaki loves to explore how we forget the magic in our world as we’re crushed by the weight of societal expectations and capitalistic progress.

The children and their parents are living in different worlds, and the truth lies somewhere between them.

It’s difficult to ascertain in Miyazaki’s films whether the magical elements occurring on screen are real — or a figment of the beautiful imaginations of children untainted by responsibility, unjaded by social pressures of adolescence, unburdened by the backbreaking demands of adulthood.

Ask any child and they’d tell you the magic is real. These are stories told through the eyes of children. To them, massive oak trees sprouting overnight, goldfish that turn into little girls, and soot gremlins inhabiting shadowy corners are, of course, a facet of reality. Their reality. If you look more closely, however, you can see the adults skirting the edges of these films are also affected in small ways by the natural magical world.

The children and their parents are living in different worlds, and the truth lies somewhere between them.

“The most important thing is, I think, that even within such an environment, children grow up, they learn to love and they enjoy living in that environment,” Miyazaki told FanBolt in 2010. “I think what is most important is that parents and children see each other as being very valuable and very precious to each other.”

Miyazaki believes imagination is important for people of all ages, Miyazaki told Tom Mes of Midnight Eye. “We shouldn’t stick too close to everyday reality but give room to the reality of the heart, of the mind, and of the imagination. Those things can help us in life.” But he also urges caution about “fantasy,” which he likens to virtual reality. “We need to be open to the powers of imagination, which brings something useful to reality. Virtual reality can imprison people. It’s a dilemma I struggle with in my work, that balance between imaginary worlds and virtual worlds.”

And so as we watch films like Ponyo, we have to ask ourselves, is it the children and their fantastical adventures who are denying reality, or their parents?

As the film’s fantasy world comes to life, many of Ponyo’s adults–from Sosuke’s mother, Lisa, to the residents of the old folks’ home where she works–meet the bending of nature’s laws with the same sort of nonplussed glee as the children. Sosuke’s father, Koichi, watches from the deck of his long-haul freighter, remarking with awe at the towering size of the moon. Though the retiree Toki surrounds herself with skepticism, a barrier against the unknowable dangers of a world that’s passed her by, none of the other adults show signs of fear or anxiety at the improbable events brought about by the girl Ponyo’s mischief and magic. They’re a reflection of the childhood wonder that so fascinates Miyazaki. Ancient Devonian Era fish swim beneath their feet by the film’s end, representing the past meeting with the future — childhood colliding with adulthood. Humanity’s innate sense of wonder, its yearning for some higher purpose, our secret wish that magic is real, removed from the choking expectations and routines of modern society.

Contrast that with My Neighbor Totoro’s Tatsuo Kusakabe, father of Satsuki and Mei, who encourages his children to explore the natural world around their new home. He speaks respectfully of the relationship between forest spirits and humans, and listens with a kind ear to his daughters’ stories of totoros and soot sprites. But he also remains distracted from the magic occurring around him by the demands of raising two children on his own while juggling a busy career as an archaeologist.

What I took from them during that maelstrom between childhood and adulthood was remarkably different than when I started watching My Neighbor Totoro with my children years later.

Even in Kusakabe’s career, Miyazaki seems to be trading a sly wink with his audience. The harried father spends his evenings mining the past, trying to uncover forgotten truths, but at the expense of not noticing what’s going on in the present. While he works inside, swatting flies away from the lamp on his desk, back bent and stiff over piling spreadsheets, Kusakabe’s children join three totoros outside. Together the five of them magically grow several acorns into a towering, megalithic tree, casting a long shadow over their father’s forgotten youth.

This phenomenon is not contained to the parents within the films, but viewers as well. I fell in love with Miyazaki’s films in my late teens. However, what I took from them during that maelstrom between childhood and adulthood was remarkably different than when I started watching My Neighbor Totoro with my children years later. An experience that felt grounded in escapism to a teenager revealed itself to be a nostalgic reminder to not to willingly trade innocence for responsibility. Seeing my children reflected in Satsuki and Mei reminded me of the reality of imagination. I don’t see my daughter’s plush toys come to life; her adventures look like rambunctious play; and the monsters under her bed are just shadows and toys to me — but they represent loneliness, bravery, and worry just the same. It’s by connecting with these emotions that we learn to understand our world, and that doesn’t go away no matter your age.

It’s not an inherent innocence or naivety that opens children to the magical world of the totoros, argues Austin Gilkeson for Tor.com, for they are flawed and vulnerable, just like adults. Rather, it’s that they don’t know the door to the spirit world is supposed to be closed. “Mr. Kusakabe may need to visit the camphor tree shrine to speak to Totoro, but Satsuki and Mei don’t — they can find their way to him from their own yard,” Gilkeson points out. “Adults see what they expect to see. Children have few expectations for what is and isn’t lurking out there in the world; they’re the ones who glimpse shadows moving in the gloom of an abandoned amusement park, a goldfish returned in the shape of a girl, or a small white spirit walking through the grass.”

Remember this the next time you shush away your daughter who fears lurking shadows, or tells you of the wolf howling outside her window. To you, they are only shadows and sounds of a passing truck — but to her they are real.

Undercutting Satsuki and Mei’s childhood is the spectre of their mother’s illness. Confined to nearby Shichikokuyama Hospital, Yasuko Kusakabe battles tuberculosis. Like Satsuke and Mei, Miyazaki spent much of his childhood visiting his mother’s bedside at a hospital while she battled spinal tuberculosis, wishing for eight years she could come home.

“The interesting thing [about My Neighbor Totoro] is that you gradually realize that the girls are in a kind of crisis,” describes Margaret Talbot, speaking to The New Yorker, “their mother is in the hospital for a lengthy stay, and they are having to cope with her absence and the unpredictability of her return. Their fantasy world is one that they enter partly to find comfort. The creatures aren’t as anthropomorphized as in a Disney film — they don’t talk, and their sheer size suggests that they aren’t quite tamable — and the girls are not as idealized. The little one throws a tantrum, the older one yells at her. They are emotionally vulnerable but physically brave, as well as powerfully imaginative and sometimes spacey — like real kids.”

There is a blurred line between bravery and blissful, youthful naivety. To escape the family’s crisis, Tatsuo Kusakabe throws himself into his work. He intuits that the idyllic village to which they’ve relocated will protect his children, which, of course, they do in his absence during the film’s emotional climax. The children, however, escape into something much more daring than mundane work.

At one point, Granny, a neighbour who cares for the girls when Kusakabe’s in Tokyo for work, helps the girls harvest vegetables. “They’re very good for you,” says Granny. “They’ve soaked up lots of vitamins and sunshine.” Satsuki asks if they can help her mother recover. “Of course they would,” Granny assures the girls. “If your mom eats my vegetables, I bet she’d get well right away.” Perhaps in Totoro’s magical world, such words are true.

However, 11-year-old Satsuki already begins to express doubts about the reality of Totoro’s world. When Mei visits her at school, Satsuki is embarrassed when her younger sister begins talking about Totoro. The morning after sprouting the enormous tree, Satsuki and Mei rush to their garden to find the acorns they planted have indeed sprouted.

Satsuki: I thought it was a dream!

Mei: It wasn’t a dream!

Satsuki: I thought it was a dream!

Mei: It wasn’t a dream.

Both girls: Yay! We did it!

Was it a dream? Who is correct?

“Call them kami, or gods, or spirits, or woodland creatures, or Mother Nature, or the environment,” says Gilkeson. “They are there if we know where to look, and their gifts for us are ready if we know how to ask. We have only to approach them as a child would — like Satsuki, Mei, Chihiro, and Sosuke — with open eyes and open hearts.”

There’s more to this than simply injecting joy and wonder into viewers, points out Doug Schnitzspahn at Fatherly. “The biggest reason why My Neighbor Totoro is so important to kids,” he says, “the reason they need to see it before they grow too old and jaded by the demands of young adulthood that tell them to reject everything childish, is that it’s about feeling safe. It’s as simple and as complicated as that. And once your kids see the movie, Totoro will always be there, sitting on the top of a tree branch in the back of their minds.”

Sosuke experiences his own kind of crisis. Just five years old, he’s often left on his own by his caring but overworked mother, Lisa. His father is a longshoreman who takes too many overtime shifts, and, over the course of the film, communicates with his wife and child mostly via morse code as his ship passes shore. There’s an intense closeness between Lisa and Sosuke, but also a loneliness. And so Ponyo, an effervescent ball of happiness and magic, emerges from the ocean as an imaginary friend might: instantly familiar and an immediate part of their family. As a dangerous storm rises outside, Lisa tells Sosuke that he’s the man of the house as she races out the door to help the residents of the retirement home. Sosuke, with Ponyo at his side, is unflustered.

It’s almost startling to watch a Miyazaki film about childhood and see adults accept the magical world.

The next morning Sosuke and Ponyo, now a little girl, embark on a mission to find his mother. Along the way, they run into hundreds of other villages aboard boats — there’s no panic at the fact that the moon has sunk their village beneath the ocean, just a feeling of togetherness and joy at the change. When Sosuke finally finds his mom, she’s in discussion with Ponyo’s mother, a goddess. This is the only moment among the three films when any of the parents directly acknowledges and interacts with the magical world.

It’s almost startling to watch a Miyazaki film about childhood and see adults accept the magical world. But it’s in these ways that the legendary filmmaker continues to surprise and delight us.

Contrast this with Chihiro’s journey through Yubaba’s Bathhouse in Spirited Away — a location bursting with magical creatures, but also a sense of otherworldly dread. Where Mei and Satsuki almost feel like they belong in Totoro’s world — where there’s almost no differentiation between the magical world and their own — Chihiro is an outsider in the bathhouse. Her entire quest revolves around escape and finding a way to return her parents to their true form.

Like Sosuke and the Kusakabe girls, Chihiro is left by her parents to fend for herself. Hers is a story about finding independence and companionship, in understanding that the world is a complex place, and that that status quo can never be restored as we grow up. Chihiro’s journey requires her to leave the safety of her parents, to discover a strength within herself that would have remained hidden as long as she was within their protective bubble.

“There are two scenes in Spirited Away that could be considered symbolic for the film,” Miyazaki told Mes. “One is the first scene in the back of the car, where she is really a vulnerable little girl, and the other is the final scene, where she’s full of life and has faced the whole world. Those are two portraits of Chihiro which show the development of her character.”

Despite being known for his whimsical films — many of which are filled with hope and wonder — Miyazaki shared with Xan Brooks of The Guardian an anecdote about what he described as his pessimistic views of the world. When a coworker welcomes a new child, Miyazaki said, he can’t help but wish for a good future for them. “Because I can’t tell that child, ‘Oh, you shouldn’t have come into this life.’ And yet I know the world is heading in a bad direction. So with those conflicting thoughts in mind, I think about what kind of films I should be making.”

When asked if this is why he makes films, Miyazaki agreed. “I believe that children’s souls are the inheritors of historical memory from previous generations. It’s just that as they grow older and experience the everyday world that memory sinks lower and lower. I feel I need to make a film that reaches down to that level.” If he could make such a film, Miyazaki said, he could die happy.

“Is someone different at age 18 or 60?” Miyazaki once asked — a curious question, but he supplied his own quick answer: “I believe one stays the same.”

The magic’s out there, we just need to open our eyes.

This piece was originally published in Uncanny Magazine #38.