Astrolabe 32: Meet the women who defined the sound of a generation

A look back at the revolutionary video game soundtracks of the 90s, a couple of personal histories, and the souls of demons

Inaudible Memories

In early 2017, Mark Brown, founder of YouTube channel Game Maker’s Toolkit, wrote a popular Twitter thread raising awareness of the influential work by female composers in the games industry.

“Many of your favourite Japanese games were scored by women!” Brown said. “They're just not as famous as [Koji] Kondo or Uematsu.” Brown continued by name dropping a staggering number of influential game composers. None quite as famous as Uematsu, but each having left an indelible influence on the industry—like Metal Gear Solid’s Rika Muranaka, or Yuka Tsujiyoko of Fire Emblem fame—and many continuing to release highly regarded work today—like Yoko Shimomura, who’s worked on everything from Street Fighter II to Kingdom Hearts to Final Fantasy XV.

“These women have shaped the history of Japanese games and deserve more recognition,” Brown said.

Men like Sakaguchi and Horii are most often considered the face of Japanese RPGs, and it’s easy to compile a list of similar men who have shaped the genre over the years—but the reality, as Brown points out, is that JRPGs and gaming have been heavily influenced by women from their very earliest days when Kazuko Shibuya and Rieko Kodama were creating Final Fantasy and Phantasy Star.

From designing sprites to writing stories to directing games, the legacy of many women shape the JRPGs we play today, but perhaps their biggest impact is on the way these games sound. Shimomura, Tsujiyoko, and other composers like Panzer Dragoon Saga’s Saori Kobayashi and Mariko Nanba, might not have the household name recognition of peers like Nobuo Uematsu or Koichi Sugiyama, but one look at any list of “best video game soundtracks of all time” will reveal their work more regularly than not.

Upon graduation from the Osaka College of Music in 1988, at just 21 years old, Yoko Shimomura began working at game developer Capcom on games like Final Fight and Street Fighter II: The World Warrior.

“She quickly became a leading member of the company’s sound team Alph Lyla and contributed to over 15 projects during her five year tenure at the company,” reported SEMO. “Most notably, she helped to popularize game music by crafting, under a pseudonym,1 all but three tracks on the blockbuster fighting game Street Fighter II for Arcades.” Like Sakaguchi writing character themes for Final Fantasy titles, Shimomura did the same for the Street Fight II cast, creating some of the most iconic video game songs in the medium’s history while she was at it. “At the core of the score’s appeal, however, were its strong pop-influenced melodies, which lent themselves to being whistled by fans all over the world.”

Shimomura cut her teeth on the JRPG genre with Capcom’s Breath of Fire before moving onto Square,2 where she gained major recognition for her work on Super Mario RPG: Legend of the Seven Stars.

The early game consoles were constrained by technical limitations requiring composers like Shimomura to rethink how they wrote and composed music. It’s a running theme through my book Fight, Magic, Items that these technical limitations were as much boon as curse—requiring creativity and new lines of thinking to over come—and spawned the chip tune genre, which is still popular today.

Instead of being able to perform their music using traditional musical instruments, Shimomura instead utilized electronically generated sounds,3 or compressed sound samples that could be arranged and played on the fly by the game console's hardware. By the 16-bit era, the consoles had more robust “sound font libraries” built into their hardware, with the Super NES providing particularly diverse and robust options. Composers could store more sound samples on the cartridge, but it used up valuable memory that could be used for other game assets like graphics or story.

The PlayStation changed the game. Instead of expensive cartridges, games shipped on cheap CDs with exponentially more storage space. Each disc could hold over 100 times as much data as the largest Super NES cartridge.4 As Final Fantasy-creator Square quickly figured out, they could ship on multiple discs, giving musicians an enormous playground. They went from swimming in the backyard kiddy pool to an Olympic-sized one.

Excerpt from Fight, Magic, Items: The History of Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest, and the Rise of Japanese RPGS in the WestThe first time I realized the potential of the CD-based format for music in games was seconds after I loaded up Wild ARMs, an early sci-fi western-themed JRPG from designer Akifumi Kaneko and developer Media.Vision.

The hand drawn anime opening was impressive. I never owned a Sega CD, so I hadn’t even been exposed to the faux-cinematics composed with in-game graphics in titles like Lunar: The Silver Star or Vay, which might’ve prepared me for the transition. But, I was coming off the Super NES, where the closest thing to a movie-like cut scene was the simple graphical trickery of Final Fantasy VI’s intro where Terra and her Magitek companions march into the snowy city of Narshe. That had been impressive enough—Wild ARMs was on a whole other level.

And what really stopped my breath was the music.

Get Fight, Magic, Items: The History of Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest, and the Rise of Japanese RPGs in the West

Musicians like Uematsu had already incorporated non-classical motifs into game music—like the spaghetti western twang of Shadow’s theme in Final Fantasy VI—but Wild Arms composer Akifumi Naruke’s introduction of live instruments, including an instantly recognizable Spanish guitar melody and a real-live human being whistling an unforgettable melody, were an elevation of JRPG music on par with the introduction of 3D graphics to the genre.

“This was ANIME in a VIDEO GAME,” said Siliconera’s Joel Couture in a piece exploring Wild ARMs’s musical impact. “It’s that soft, soothing guitar accompanied by a gentle whistling that set the musical tone for the game, capturing its Wild West feel and creating this resonance within me.” The increasing sense of adventure dragged Courture into the game before it had even started, with a sound he’d never heard in a game before: not synthesized sound samples of instruments, but real instruments.

“I have a deep love of chiptunes,” he continued, “and have many, many fond memories of the soundtracks of many an NES and SNES RPG, but this was a revelation for me at the time. This movement from the game-y sounds of Final Fantasy VI to highly realistic music had me floored with the possibilities in games at the time. This Western-themed track just promised so much emotional connection, excitement, danger, and adventure that it was impossible to look away.”

Naruke’s Wild ARMs kicked off an avalanche of impressive opening songs on the PlayStation that carried through to console generations beyond. “Each and every track on the Wild ARMs soundtrack is marvelous,” said TechnoBuffalo’s Ron Duwell, “and composer Michiko Naruke should be granted the same immortal status of some of her peers because of it.”

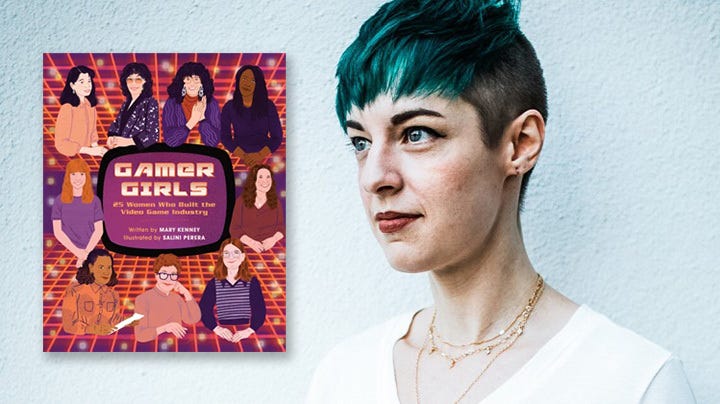

It’s vital to remember these stories, Mary Kenney told me. But it doesn’t happen automatically.

“I think the first step is to credit them,” she continued. “In many cases, women were left out of the credits of games they worked on, or their contributions were downplayed. Giving everyone on the dev team their proper credit and inviting them to share their knowledge and experiences—in conferences, panels, books, university courses, and so on—is how we get to see the diverse teams bringing us our favorite games.”

Kenney, a games writer and author of Gamer Girls, a YA nonfiction book about the women who built the video games industry (which I heartily recommended in Astrolabe 26), believes it’s time to retire the idea of video game auteurs. “Video games are very rarely made by an individual,” she told me. “and it's impossible to separate out who contributed what to any given project.

“I’ll give you an example: in one of my earliest projects, I wrote a romantic scene between two characters (The Walking Dead: The Final Season, Clementine and Violet). That scene is about as close as one could get to being "mine”—I plotted the beat, wrote the script, and pitched the idea for those two characters to be together. Yet there are about a thousand moments in the scene that I didn't make. I didn't build the character models or the rooftop on which they decided to have this conversation. At one point in the scene, the characters hold hands. I didn't write that; the animator added it. There's a stargazing puzzle in the middle that was built by a designer. We're building experiences together, and creativity from women like Yoko Shimomura and Rieko Kodama shaped the norms we've all come to love and expect from JRPGs.”

There are amazing creative directors and artists across the industry whose visions and ideas have shaped the games we love—but they didn’t create everything. “Giving credit to teams rather than leads is a great way to see just how many brilliant people there are in this industry—many of them women.”

To find the beginning of women like Naruke and Shimomura influencing video game music, you must go back to the beginning of video game music. They’re one and the same.

In a piece called “The Women Who Invented Video Game Music,” WIRED’s Dia Lacina paints a picture of late ’80s Japan at the offices of game development icons like Capcom and Taito. “It's in this time, and in these places, where groups of women composers, often some of the earliest sound team hires, laid the harmonic foundation for many of video gaming's most enduring franchises with their infectious earworms,” she described so clearly you can smell the cigarette smoke in the air. “Their work filled living rooms, and their soundtracks collided against one another in crowded arcades, urging on the cheers of quarter-pumping gamers backgrounded by the racket of change machines. Soundtracks rapidly became as crucial as the games themselves.”

In their footsteps are new musicians writing the future of video game music one note at a time.

Video games at the time were not as visually impressive as Hollywood blockbusters. They did not have the razor-sharp prose of the best novels. But I’ll be damned if they didn’t have soundtracks that could match any other media in the world—and these women were right there at the top, leading the way.

If you enjoyed this peek at video game history, consider picking up a copy of Mary Kenney’s Gamer Girls: 25 Women Who Built the Video Game Industry and my deep dive into the origin and impact of Japanese RPGs, Fight, Magic, Items: The History of Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest, and the Rise of Japanese RPGs in the West.

Out & About

Out & About is where I highlight my work around the web—some recent and some old favourites.It’s my print debut! After a few years writing about games online, I’m so thrilled to be featured in Game Informer’s current issue. My feature, “The Age of Nostalgia,” is a deep dive into fans who are “demaking” modern games by turning them into 8-, 16-, and 32-bit experiences.

For this piece, I spoke to Game Boy Demakes, Lilith Walther, and 64 Bits about their detailed and painstaking "demakes" of modern games like Elden Ring, Kirby and the Forgotten Land, Mass Effect, and Bloodborne. It should be available online soon.

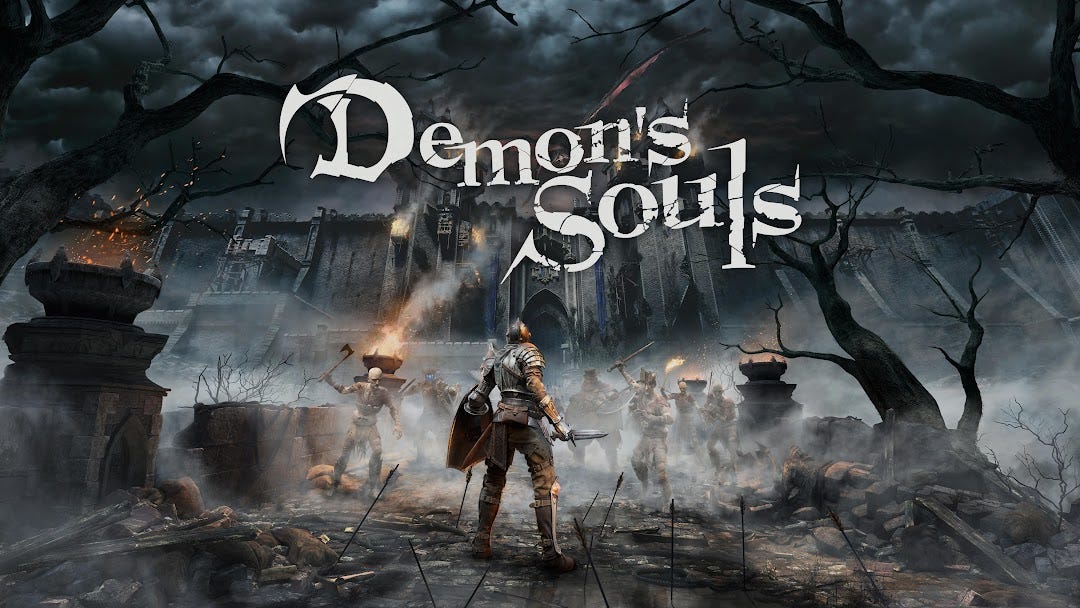

LTTP—Demon’s Souls (2020, PlayStation 5)

LTTP (Late to the Party) is a regular column where I let Twitter decide which retro game I’ll play for an hour. Do your worst, Twitter!This issue’s LTTP breaks in my new PlayStation 5 with a brilliant remake of a stone cold classic that I’ve been too scare to play for well over a decade: Demon’s Souls. How does it hold up for new players in a post-Elden Ring world? Let’s find out.

After wrapping up God of War (2018)—which is incredible running in 4K/60fps on the PlayStation 5, but ultimately a last gen expereince—I wanted a title that really showcased everything the PlayStation 5 has to offer. I turned to Bluepoint Games’s 2020 remake of Demon’s Souls. Since it wasn’t trying to target last generation consoles (like its newer counterpart Elden Ring), it’s an audiovisual powerhouse, and featured graphics and sound design that immediately wowed me, and didn’t let up over the course of my 30 hour playthrough.

I understand many longtime fans are unhappy with Bluepoint’s take on the game’s visuals and world design, but for a newcomer like me, the fantasy world they’ve crafted—jam packed with details and rendered in astounding fidelity compared to pretty much anything else on the market—feels like magic. The opening are, pictured below, was particularly impressive with its dramatic lighting, and lush, overgrown brickwork. Not a smooth surface in sight, and with impressive dynamic lighting throughout.

The Soulsbourne games have a well earned reputation for difficulty. When I first played Elden Ring last year, though, several years after a failed attempt at Dark Souls 2, I was surprised to find myself—a difficulty-averse player—enjoying it immensely. Taking many of the lessons I learned in my 150 hour playthrough of Elden Ring, I jumped into Demon’s Souls with a mix of trepidation and curiousity. Could I succeed without the summonable companions that made Elden Ring so accessible? How would I grind levels without an open world? Demon’s Souls is a very different game than Elden Ring in the way it’s structured—my playthrough was about 1/5 as long as my Elden Ring playthrough, for instance—but the core lesson of “patience over progress” was more than enough to make Demon’s Souls not a cake walk, but a perfectly enjoyable experience.

Just like with Elden Ring, I cruised through many of the bosses on my first try (even the dreaded Flamelurker and Maneaters) with the help of magic (what the Demon’s Souls community calls “easy mode," which checks out) and judicious use of the schoolyard gossip mill (i.e. the Demon’s Souls wiki and Reddit) to help me prepare. In fact, I recently struggled far more with Metroid Prime Remaster’s penultimate boss—Meta Ridley—than with any boss in Demon’s Souls (or Elden Ring, for that matter.) It’s not the first time I’ve compared the approach to difficulty in Miyazaki’s games to Metroid:

This isn’t to say I’m great at video games or achieved anything remarkable here—I simply used the tools offered by the game to create advantage for myself. Rather, it’s an encouragement for players to give the Soulsbourne games a shot, even if you don’t like difficult games, or have been scared off by the series’ reputation in the past. I used to feel the same way, but now, after conquering two of the titles, I feel like I can take on any game in the series—even the harder ones—by practicing the core principals and ideas that undergird creator Hidetaka Miyazaki’s games. Despite its aging bones, Demon’s Souls is a marvel of next gen gaming and remains a compelling history lesson for an ouerve that would go onto change gaming. And you won’t find a prettier game out there.

Demon’s Souls was released by Bluepoint Games and Sony for the PlayStation 5 in 2020. The original version was released on PlayStation 3 in 2009. Recommended Reads—Bit by Bit by Andrew Ervin and Baldur’s Gate II by Matt Bell

If you’ve read Fight, Magic, Items, you’ll know I love a good story that ties together personal experience and topical history. As video games mature, we can learn an immense amount about them, their creators, and their fans by looking back to our youthful experiences as we participated directly in the history as it was being made. Matt Bell’s Baldur’s Gate II and Andrew Ervin’s Bit by Bit: How Video Games Transformed Our World both execute on this concept brilliantly with their well-balanced personal anecdotes and well-researched history. Not only do both books explore the history and the legacy of the games, but they also reveal how and why people are affected so dramatically, and long-lastingly, by video games.

Highly recommended, both. Ervin’s book covers a wide variety of games, and looks at the industry/fandom holistically (if not exhaustively), while Bell’s book narrows down specifically on BioWare’s classic RPG Baldur’s Gate II, yet remains compulsive and interesting even if you’re not familiar with the game.

Bit by Bit by Andrew Ervin is available from Basic Books, and Matt Bell’s Baldur’s Gate II is available from Boss Fight Books.

Quest Markers

Quest Markers is a collection of the coolest stuff I’ve read around the web lately.- The Fabulist in the Woods (Vulture)

- 1993’s Super Mario Bros. is so much better than the new animated movie (Polygon)

- Water in video games has never looked wetter. Er, better. (Washington Post)

- Why video game protagonists have become so chatty (Polygon)

- Soapbox: Why Aren't There More Books About Games? (Nintendo Life)

- Meet the Indigenous Women Leading Conservation Efforts in the Great Barrier Reef (Traveler)

- We're Losing More Than We Realize When These Classic Pokémon Games Get Pulled (Kotaku)

- 11 Juno Award nominees share their favourite books (CBC)

- Why Video Game (Fan)zines Still Matter In 2023 (Time Extension)

- Fabulous Fungi: On the Endless Possibilities of the Mushroom (Literary Hub)

- De La Soul’s Music Is Here to Stay (For Now) (Vulture)

- Final Fantasy XVI Is What Happens When Developers Grow Up (WIRED)

- HBO's The Last Of Us Showcases The Real Queer Agenda: To Live Long And Happily (Gamespot)

- A World Without Men (The Cut)

- Ultima Creator Richard Garriott Recounts The Gory Tale Of Getting His First Game Manufactured (Time Extension)

- Why Are Video Games So Afraid Of Everyday Life? (Kotaku)

- Why the Floppy Disk Just Won’t Die (WIRED)

- Breath of the Wild Is Still Switch’s Best Game, and It’s Not That Close (Escapist)

- Matthias Linda's seven year quest to make retro JRPG Chained Echoes (Game Developer)

- Into the Myst (Inverse)

- Christopher Judge is blazing a new trail (Washington Post)

End Step

Substack recently launched Notes, which I’m quite excited about. They function similarly to Twitter—a great place for short form content, updates, and bonus material for Astrolabe—without actively supressing longform content (like Twitter does.) How do you readers feel about Notes? Let me know!

Support

There are lots of ways to support Astrolabe and my other work. Check ‘em out!

Keep In Touch

Enjoy Astrolabe? Want more SFF and retro gaming goodies? You can find me on Twitter and my website.

Credits

Astrolabe banner photo by Shot by Cerqueira on Unsplash

It was not uncommon for Japanese artists and programmers in video games to be credited under a pseudonym back then. ↩

Who, perhaps not coincidentally, published Breath of Fire in North America. ↩

Generated by a computer chip in the game console, thus “chip tune.” ↩

Tales of Phantasia and Star Ocean, neither of which was officially released in North America, both clocked in at 6 megabytes (48 megabits). ↩