Astrolabe Gaiden: How I write and revise non-fiction

A writer’s journey is never complete. There’s always more and more and more to learn. One of the most important steps I’ve taken during my journey was to accept the inevitability and usefulness of revisions.

I used to get paralyzed while drafting because I feared revisions. I was so determined to get the right words the first time… that I just wouldn’t write anything at all. I saw revisions and edits as a failure to execute on my ideas. I was impatient, and it felt like the time spent on that first draft was wasted or inefficient if I had to revise. As I wrote more and more—and eventually started working with some great editors and creative partners—I began to not only understand the importance of revision, but completely reversed my opinion on the process. The concept of revision freed me to write faster than ever, because I realized it doesn’t matter if I get the right words the first time around, because I can always fix them later.

A first draft is the chance to tell yourself the story. Revisions are the time to find the right words for your readers.

There’s not a lot out there to help developing writers understand how to revise. We’re treated to beautiful essays, articles, reviews, and long-form pieces all the time, but it’s easy miss all the hard work that went into getting them right. We talk a lot about Instagram Envy, where we only see the highlights from our friends’s lives, and none of the mess around the edges. We don’t like to show off how hard we had to work for our success. We hide the stuff that hit the cutting room floor. But creative work requires so much trial and error. So much failure and growth. Writing’s no different. We only read an essay once it’s been agonized over for hours—revised and polished until it’s perfect. As a young writer, I thought this was how my first drafts were supposed to come out. Perfectly gleaming.

I didn’t understand the process that actually went into polishing a gem.

So, I want to pull back the curtain a bit on my recent piece, “Timeless: A History of Chrono Trigger,” to show you how it came together through various phases, and what it looks like to draft and revise a large essay. I hope this can be useful for writers who are currently experiencing the feelings I had 5-10 years ago.

When I first start conceptualizing a new long-form piece, I begin with a single idea, and spend time thinking about my angle—what I’m going to bring to it as a writer, and what kind of feeling I want to leave the reader with. For “Timeless: A History of Chrono Trigger,” I wanted to impart upon the reader my love for the game and immense respect for its creators. With those as my guiding principals, I realized the essay would take on two faces: well-researched history, and subjective anecdotal analysis based on my personal experience.

At this point, I created a blank Google Doc file and started jotting down notes. I generally begin with a rough outline, but even this early in the process I’ll start writing sentences or even full passages that form the narrative’s foundation. This outline is going to give me the piece’s overall shape and structure.

The more emotive, subjective passages came easy—I’ve spent a lot of time with the game throughout my life, and I have a lot of opinions and perspective to share. I’ll write myself some bulleted notes covering these thoughts, and roughly group them based on how I see the overall piece coming together.

I follow this up with a lot of reading and research. This gives me the idea of how the factual story will shape up, and how the story will be told from a thematic and research-based perspective. I’ll gather lots of quotes at this point, and place them here and there in the outline depending on where I think they might be used. In the end, quotes move around a lot as the shape of the piece changes, and I find the overall narrative.

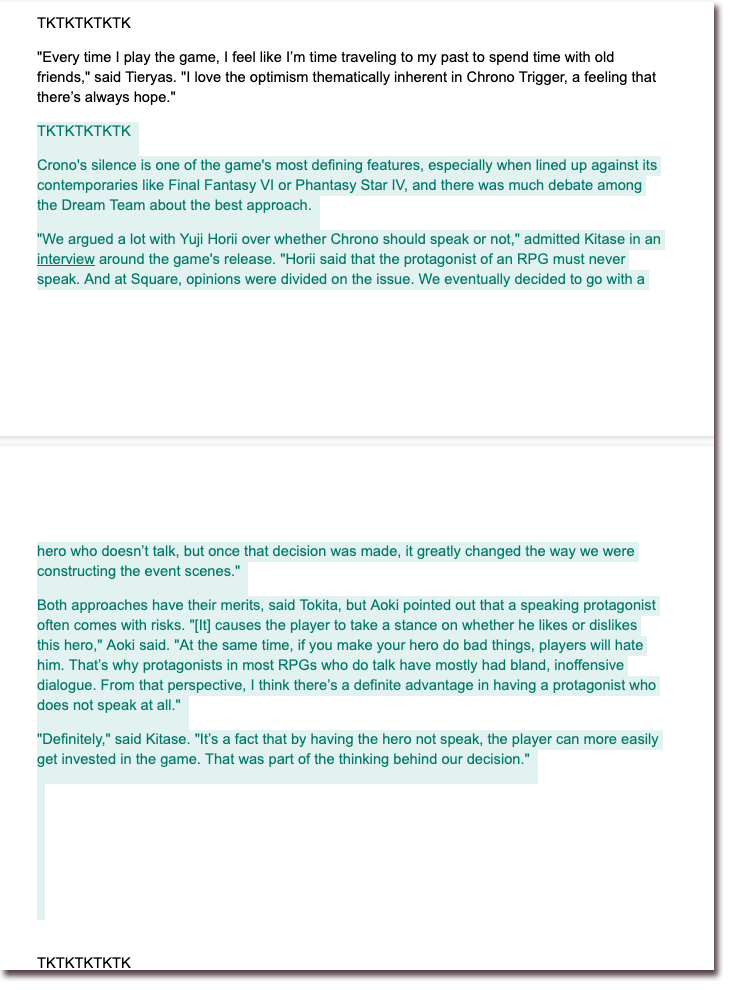

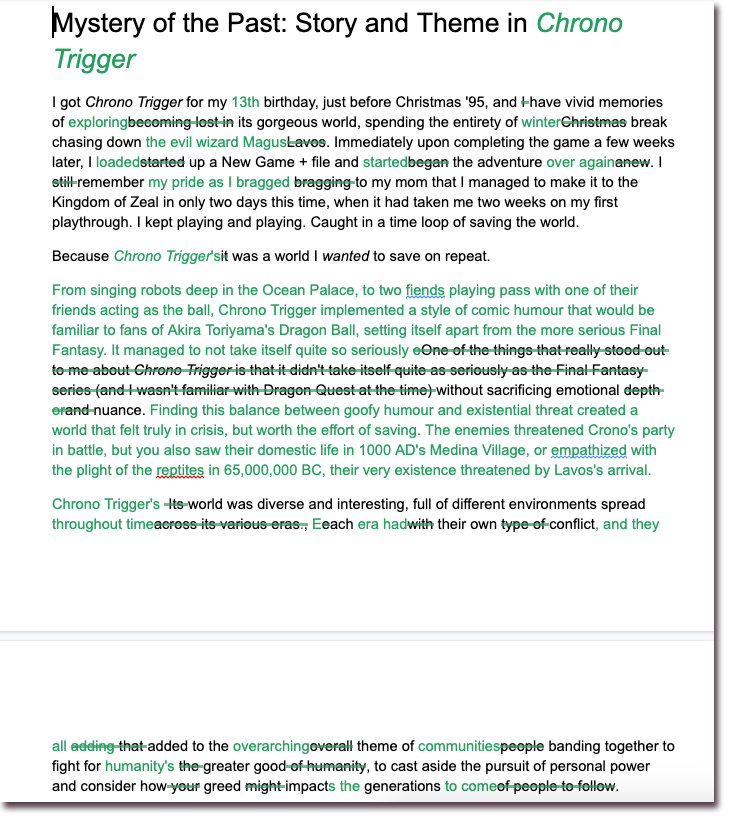

I have a very non-linear way of writing non-fiction, especially long, researched pieces like this one. These two screenshots are an example of how I assemble the essay’s narrative and structure once piece at a time.

Like working on a puzzle, I flit around to work on whatever excites me or has the best momentum. The pieces are strewn before me on the table, and sometimes I’m working on the cottage, sometimes it’s the sunset, and sometimes it’s the mountains. Generally my research guides the piece, and as I get further into that, each section starts to take shape independently. This helps me weave ideas and themes throughout the whole piece.

In the example above, you can see that I’ve framed this section with a personal story about my attachment to the game, and then I’ve found some relevant quotes that add to the overall conversation about Chrono Trigger’s tone/story, but they don’t flow nicely into each other. You can also see that some of what I’ve written is very close to the final product, while other thoughts are still in note form (but using language that will appear in the published draft).

You’ll also notice a lot of “TKTKTKTK” marks throughout the draft. Any time I know the piece needs something else—whether its a whole section, or just a transitional paragraph, I leave myself a “TKTKTKTK” mark, reminding me that I need to go back to fill it in. Searching for “TK” in my document makes it really easy to find any spots that I still need to complete.

Once I get a sense for where there’re holes, I start doing research specifically to fill them. This specific piece required a lot of research, and features stories, quotes, and facts derived from dozens of interviews, pre- and post-release material, and official documentation.

Once all those holes are filled, I’ve got a decent but messy essay. I’ve told myself the story, I’ve justified it with my research, and now I need to figure out how to find the right words for my readers.

As I said above, a first draft is your opportunity to tell yourself the story—to figure out the shape and structure of the narrative, to find its voice, and understand what you’re trying to say. I like to get beta readers involved very early. I’m not precious about words, but I do find that the more revisions I do by myself, the more married I become to my words and choices. By getting beta readers involved after the first draft, I find my work more malleable, and it’s much easier to fix structural or thematic issues than after several rounds of revisions.

Now, I’ve got a lump of clay that’s vaguely Chrono Trigger shaped, and my job is to shave off excess, adding muscle and definition where needed. This is the time when I send the full draft to my first round of beta readers. They provide feedback, and then I jump into a full revision.

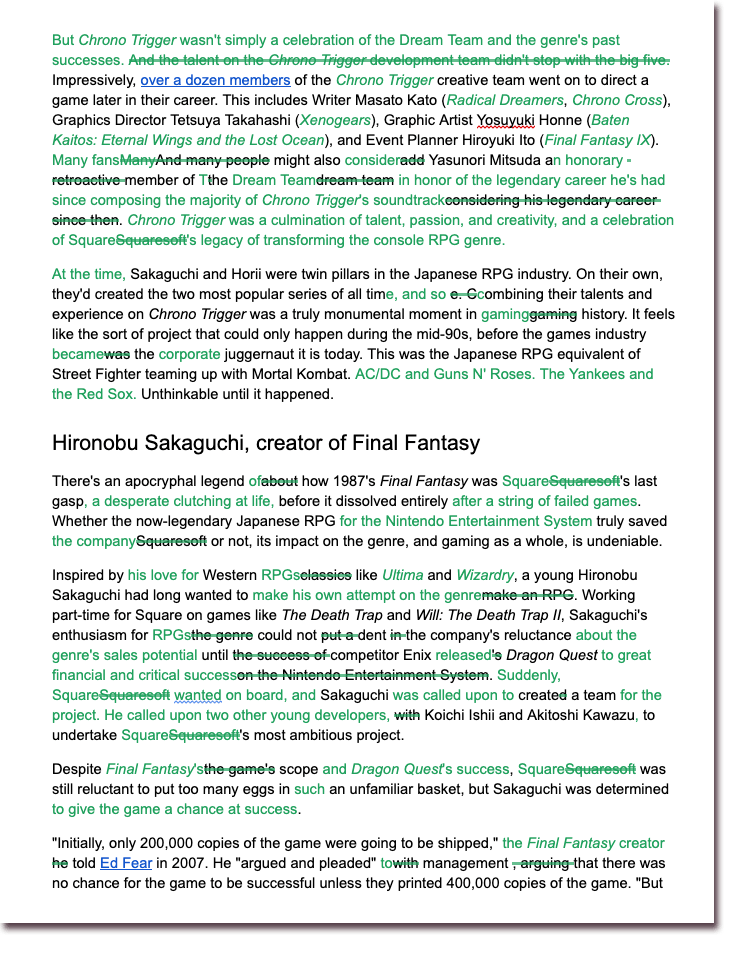

Here’s a screenshot of my first round of revisions on the piece:

There’s a lot going on here—from shoring up my description of the impressive Chrono Trigger development team, to basic copy edits, and polishing/tightening up the language. It’s not unusual for pretty much every page of revisions to look like this on my first round of edits. I spend a lot of time just getting words down on the page for my first draft, without a lot of care for craft. So this first pass is all about polishing off the rough edges and understanding how to make the content read nicely.

With this next example, I’m returning to the section I started with, to see how it evolved through the first draft and the first round of revision. This illustrates how my first draft skimmed over some content that needed to be fleshed out on a later pass. One of my early readers said they wanted a more concrete example of how Chrono Trigger used humour to set itself apart from Final Fantasy, and what that meant for the game over all.

Digging into this also allowed me to explore some specific touchstones in the game, unique elements that help set it apart from other games of the time. A huge part of tapping into nostalgia—or explaining nostalgia to those unfamiliar with the source—comes from highlighting specific elements that appear solely in Chrono Trigger. Everybody who played the game will remember their delighted surprised when the ball turned out to be a monster.

Once I’ve completed this revision, which will hopefully fill most of the holes, shore up weak areas, and trim a lot of unnecessary or redundant material, I’ll ship it off to another beta reader or two—someone who’s already read the piece, and somebody who hasn’t. In this stage, I’m focusing on really polishing the copy, and tightening it up as much as I can. I find my first round of revisions usually increases word count, where the second and third revisions reduce it dramatically.

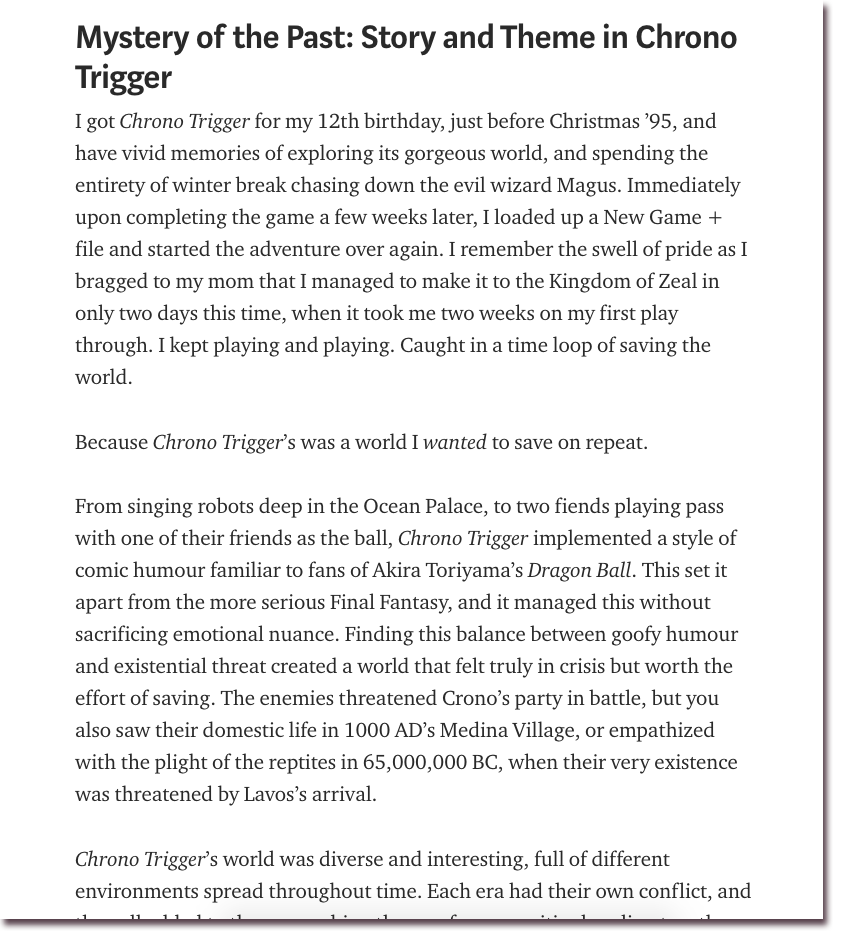

This is what the final, published version looks like:

(You’ll notice I got my age wrong in my first draft! Haha. Copyedits are important.)

My process generally breaks down like this:

- First draft—This is something I piece together in a very non-linear way, like the puzzle I described above.

- Beta readers—I’ll send the piece out to a couple of beta readers. Often, I haven’t even read through the finished draft.

- First revision—Using beta reader feedback, I’ll make structural changes, fill holes, cut out redundancies, etc. I’m not worried about copy/clean prose at this point.

- Second revision—Now I’ll do a solo pass to clean up my copy. This is generally the first time I’ll read the piece beginning-to-end in a linear way.

- Another round of beta readers—I’ll usually bring back a beta reader or two, and try to get some fresh eyes on a piece. At this point I’m trying to find any glaring holes.

- Third Revision—Addressing feedback from second round of beta readers. This is usually much quicker than the first round of beta feedback.

- Polish pass—I’ll go through on my own to do a line-level copy edit. I also trim off the rest of the fat. This is when I cut all my darlings—those little lines or passages that I love, but also know in my heart don’t really belong.

If I’m working with an editor, I’ll generally send it to them after my second round of revisions. I’ll have pretty clean copy by then, and I generally like to send something a little fatty, so my editor has a chance to shape the piece for their audience.

That’s it! It’s done!

Time to celebrate with your beverage of choice. It’s beer, for me.

Drafting and revision methods are unique to each writer, and I’m not suggesting you take anything wholesale from my examples above to apply to your own work, but I do hope you take a simple lesson from this: Just as we’re all born wrinkly and defenceless, guided and raised by our parents or families, friends and communities, writing rarely comes out perfectly formed and needs a lot of work to grow. No matter how perfect that piece you read in your favourite magazine, it started somewhere else and a lot of effort went into turning it from a raw gemstone into a polished jewel.

It would’ve saved me years of writing agony and self doubt to be able to see the work that others put into their writing. Very few writers produce high quality first drafts. While it may seem obvious to a lot of people, drafting is only the first step, and once you come to grips with revisions, and start to understand how to use them to shape and mould your work, you find an amazing sense of freedom. Revisions aren’t about right or wrong, they’re about improvement and evolution.

Member discussion