VGHW Excerpt: How Kazuko Shibuya's survived the "end times" and changed pixel art forever

"Gamer Girls" author Mary Kenney explores the Shibuya's groundbreaking work, the end of the end times, and the creative freedom of technical limitations

Welcome to Video Game History Week! In honour of the first anniversary of my book Fight, Magic, Items: The History of Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest, and the Rise of Japanese RPGs in the West, Astrolabe is celebrating video game history with a plethora of stories, features, lists, and interviews about video games, the people who make them, and the people who write about them.

Fight, Magic, Items is on sale! Use the code “LEVELUP” at checkout to get 20% off a physical copy through the Running Press website!

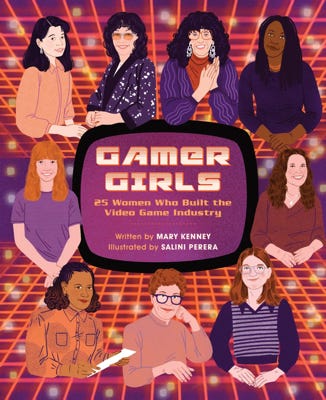

Excerpt from Gamer Girls: 25 Women Who Built the Video Game Industry by Mary Kenney

What happens when you land your dream job only to realize that it isn’t really what you want to do for the rest of your life? If you’re Kazuko Shibuya, you leave that job to find a new one, and along the way help define the art and animation of one of the most important games of all time: Final Fantasy.

The Hobby That Became a Dream

Important aside: All interviews with Kazuko were originally done in Japanese and have been translated into English. Since language is weird, translations may not match up perfectly with everything expressed in the original language. Keep in mind that the translator is often trying to capture Kazuko’s intent rather than produce a perfect translation. Okay, aside over.

Kazuko was born in 1965, just three years after the first video game, Spacewar!, launched on the DEC PDP-1 minicomputer. Video games weren’t part of her life growing up, but anime was. In middle school, she spent her spare time doodling illustrations and animations from her favorite anime, Space Battleship Yamato and Galaxy Express 999. As a teenager, she enrolled in a technical school and worked part-time in a studio, where she got to work on anime like Area 88, Transformers, and Obake no Q-taro. It was a great opportunity, but she didn’t find the day-to-day work of an animator fun. She told one of her professors that she wasn’t sure whether she wanted to be an animator anymore. Then, in 1986, a game studio looking to improve its art and animation reached out to her. The company’s name was Square, and Kazuko’s life changed.

When Kazuko joined Square, it wasn’t the behemoth publisher known today as Square Enix. It was a much smaller studio focused on making games. Kazuko was twenty-one years old, and she wasn’t a gamer; she hadn’t played anything Square made. Her family might have owned a Nintendo Famicom, but even if they did, she couldn’t remember playing with it. “Even today,” she said, in a 2013 interview with 4gamer, “I don’t play games at all.” Even so, she decided to take the job, and a year later, Square began work on one of the longest-lasting, most influential, most beloved series in gaming. The project’s name was FF, at the time, and later it was named Final Fantasy.

“Those Days Definitely Seemed Like End Times”

There is a legend about Final Fantasy that’s so ubiquitous among gamer and pop culture communities, I learned it as a fact in graduate school. The story goes that in the mid-1980s, Square was on the verge of financial disaster and about to close its doors forever. The beleaguered gamedevs at Square pitched one final game, their last mark on the industry before they lost everything. They named it Final Fantasy because it was the last game Square would ever make. Then, in a fortuitous twist, the game was so wildly successful and beloved that it singlehandedly saved Square and all of the developers’ careers. It’s a great story, but it’s not true.

In 2015, Hironobu Sakaguchi, the gamedev credited with the creation of the first Final Fantasy game, cleared up the rumor-turned-legend while speaking at the Replaying Japan conference in Kyoto. The real reason for Final Fantasy’s name is this: The team wanted to name the game something that would abbreviate to “FF,” because it sounds good in Japanese. “Fantasy” was the obvious pick for one of those f-words, since they were making a fantasy game. The other word took a little longer to nail down. Fighting Fantasy was the first title, but a series of role-playing books already had that name, so that wouldn’t work. The team eventually settled on the title we know and love today, Final Fantasy.

That’s not to say every part of the legend is untrue. “Those days definitely seemed like end times,” Sakaguchi said at the conference. Square had made more than twenty games by then, including The Death Trap and King’s Knight. Though The Death Trap and its sequel sold more than 100,000 copies, none of Square’s other games were runaway hits, and bankruptcy loomed as a real possibility.

Very few people at Square liked the idea of creating a fantasy RPG. They didn’t think it would sell well. Kazuko was one of the ones who wasn’t sure it would do well, but even so, she offered to help and joined the FF team as a pixel artist. If Square closed, Kazuko would have to switch jobs. Again. She didn’t want to, so she did what she does best: created fantastic art and animation she hoped would draw in the audience Final Fantasy desperately needed.

Creating game art is never easy, but creating it on early consoles was especially challenging because of the technical limitations. Kazuko was limited by the color palette the Famicom could display, only twenty-five colors on-screen at the same time. If that seems like a lot, consider how many colors can exist within a single shadow—dozens of shades of blue, gray, and black—let alone the character or creature that cast it. That’s the box in which Kazuko had to work.

She was tasked with creating character pixel art, fonts, menus, chibi characters, animations, and even monster designs. To create them for Final Fantasy, Kazuko had two major influences to draw from: the art of Yoshitaka Amano, and other games of the genre. Yoshitaka Amano was the concept artist for Final Fantasy, and he created pages and pages of ideas for monsters and other creatures that could be included in the game. Kazuko pored over this art, studying his style and larger-than-life designs, trying to figure out how to recreate his work in a limited engine. Yoshitaka didn’t have to worry about the technical limitations of the game or Famicom, but Kazuko did. Some art she recreated in pixel form, and others she designed from scratch.

The second influence was other fantasy games, like the 1986 hit Dragon Quest. Dragon Quest was made by Enix, and if you’re thinking, “Wait! Enix . . . Square . . . Square Enix?!” You’re right. The two studios merged in 2003 to become Square Enix, one of the most well-known and profitable video game publishers in the world. But in 1984, Square and Enix were fierce competitors. Kazuko was studying Dragon Quest’s characters to see the kind of competition she was up against while creating animations for Square. A character in periwinkle blue armor takes his place on the screen. His arms shift from side to side like someone doing capoeira or a very restrained dance move. His feet hop up and down, never resting. When he does move, it’s less like walking and more like a moon walk: sliding side to side, up and down, his feet setting a rhythm totally different from the rest of his body. He is the star of Dragon Quest, a hero for the ages, the one fated to defeat the Dragonlord and save the princess.

Seeing him, Kazuko thought, “Huh. Why is he doing a crab walk?”

The End of the End Times

Final Fantasy’s opening cutscene and menu—Kazuko’s creations—are iconic in the world of video games. A turreted gray castle stands proud among tiny cottages ringed by hedges. There are two massive bodies of water, connected by a river, that separate the castle from a peninsula of brilliant green earth. A pixelated character, who walks in a distinctly not-crablike way, crosses a bridge. The world shifts into black shadows and neon pink, green, and orange water. Four heroes stand on a hill beside a lake. A cape blows in the breeze and birds wheel overhead. The title appears: “FINAL FANTASY,” in elegant blue and purple.

To create the scene, Kazuko needed to get by with, in her own words, “major economizing.” Kazuko had the technical and artistic know-how to create the scene, from her time in anime, but couldn’t use the same technology that worked in television. Early consoles had limited horsepower to display things like colors, let alone loading physics, animations, and music. Game animation wasn’t even considered its own field yet. Kazuko came up with shortcuts and tricks to load in just enough information that wouldn’t overwhelm the console, controlling where the camera was pointed so the player would, hopefully, not notice.

“It turned out that working within such limited means was a good thing for me,” she said in the 2013 4gamer interview. The challenge pushed her to create art and animation the gaming world had never seen before.

It was a good thing for the game, too. Final Fantasy was praised for its art, story, design, animation, monsters—basically, for the whole package. It sold more than 500,000 copies, and Square soon greenlit a sequel. Despite the first game’s success, fewer than a dozen people were assigned to Final Fantasy II, and Kazuko was one of them. The whole team worked together in a room so small it could barely contain all their desks and chairs sitting back-to back. “It was too small, so we were always fighting!” Kazuko told 4gamer. “The programmers and the three of them in the middle were often quarreling.”

It was only after Final Fantasy II sold as well as its predecessor that Square decided to add more people to the team. That gave Kazuko the time and resources she needed to create even more monsters, battle backgrounds, and maps than she’d been able to for the first two games. It also meant higher expectations, since the series’ success was snowballing, drawing in more players than ever before. The monsters and creatures Yoshitaka Amano created were even bigger and more fantastic, and Kazuko wanted to capture them for Final Fantasy III. In many cases, that meant she needed to entirely redesign them to work on the console and fit the screen size. She succeeded, and Final Fantasy III continued to catapult the series’ success.

It’s hard to overstate how much of an impact not just the original Final Fantasy game but the entire series has had on the video game industry. There are fourteen main games and many more spinoffs, which have earned roughly $10.9 billion as of 2019. Along with the games, there is a wide range of additional Final Fantasy media and collectibles, from anime, manga, and novels to figurines, plushies, clothes, keychains, and so much more. Without Final Fantasy, we wouldn’t have equally beloved series like Kingdom Hearts, Mana, and so many more.

The days of it feeling like the “end times” at Square were over.

Leading from the Background

In her thirty-plus years in the industry, Kazuko Shibuya has made more than thirty video games and contributed as a graphic designer, director, character artist, and supervisor. Yet she doesn’t hold the same near-mythic place in the industry as the men she worked alongside when creating Final Fantasy, largely because she wasn’t credited for her work until years later. Partly because of this, she’s had fewer chances to speak publicly or in interviews. It wasn’t until 2019, after she spoke at Japan Expo in Paris, France, that she was invited to be a member of Women in Games, a community interest group for, you guessed it, women who make, support, and play video games.

Even so, Kazuko has always been generous with advice. She gives it freely to artists, aspiring game developers, and really anyone interested in her work. She’s written blogs and has risen to art director at Square Enix while mentoring upcoming artists. Her first piece of advice? Start with the fundamentals.

She also urges artists to get up from their desks and explore the world around them. To create fantasy or real worlds, artists need inspiration. Kazuko climbed Uluru, the sandstone monolith in Australia, and watched a sunset over a New Zealand mountain range. These are the moments and colors that live in her mind when she creates fantastical scenes and creatures, both in Final Fantasy and beyond. “There’s no substitute for experiencing things with your own two eyes, taking in the whole atmosphere and context directly,” she said. “A designer must hone all five of her senses. Vision, hearing, and smell and touch, too. They are all connected to creativity. The more experiences you have to draw from, the more depth you will be able to impart to your creations.”

Excerpt from Mary Kenney’s Gamer Girls: 25 Women Who Built the Video Game Industry reprinted by permission of the author and Running Press.Gamer Girls: 25 Women Who Built the Video Game Industry by Mary Kenney is available now from Running Press.

About Gamer Girls: 25 Women Who Built the Video Game Industry

Discover the women behind the video games we love—the iconic games they created, the genres they invented, the studios and companies they built—and how they changed the industry forever.

Women have always made video games, from the 1960s and the first-of-its-kind, projector-based Sumerian Game to the blockbuster Uncharted games that defined the early 2000s. Women have been behind the writing, design, scores, and engines that power one of the most influential industries out there. In Gamer Girls, now you can explore the stories of 25 of those women. Bursting with bold artwork, easy-to-read profiles, and real-life stories of the women working on games like Centipede, Final Fantasy, Halo, and more, this dynamic illustrated book shows what a huge role women have played—and will continue to play—in the creation of video games.

With additional sidebars about other influential women in the industry, as well as a glossary and additional resources page, Gamer Girls offers a look into the work and lives of influential pixel queens such as:

- Roberta Williams (one of the creators of the adventure genre)

- Mabel Addis Mergardt (the first person to write a video game)

- Muriel Tramis (the French "knight" of video games)

- Keiko Erikawa (creator of the otome genre)

- Yoko Shimomura (composer for Street Fighter, Final Fantasy, and Kingdom Hearts)

- Rebecca Heineman (first national video game tournament champion)

- Danielle Bunten Berry (creator of M.U.L.E. and early advocate for multiplayer games)

- and more!

Whether you’re a gamer girl who plays video games, a gamer girl who makes video games, or a parent raising a gamer girl, this entertaining, inspiring book will have you itching to pick up a controller or create your own video games!

About Mary Kenney

Mary Kenney writes critically acclaimed video games, long-form non-fiction, essays, and short stories. She works at Insomniac Games, where she was on the writing team for Marvel's Spider-Man: Miles Morales and Ratchet & Clank: Rift Apart, and was a lead writer on Telltale's The Walking Dead series. Before making games, she studied in the game design master's program at New York University, and she teaches narrative design at Indiana University. She was an award-winning journalist with bylines in The New York Times, Salon, and Kotaku. When not writing or gaming, she can be found buried in a book, running a tabletop RPG, or trying to keep her forest of indoor plants alive.

About Salini Perera

Salini Perera is a freelance illustrator from Toronto. She was born in Sri Lanka, raised in Scarborough, and has been making art for as long as she can remember. Now, she gets to make art for picture books, a lifelong dream come true. She lives in the city’s east end with her husband, Michael, and their two cats, Victoria and Albert.

Support

There are lots of ways to support Astrolabe and my other work. Check ‘em out!

Keep In Touch

Enjoy Astrolabe? Want more SFF and retro gaming goodies? You can find me on Twitter and my website.

Credits

Astrolabe banner photo by Shot by Cerqueira on Unsplash