VGHW Excerpt: Japanese RPGs journey to the west with a bang in Fight, Magic, Items. Literally.

From chain smoking in a Denny's, to a volcanic explosion, and a massive Nintendo Power giveaway, this Fight, Magic, Items excerpt chronicles Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest's tumultuous journey west

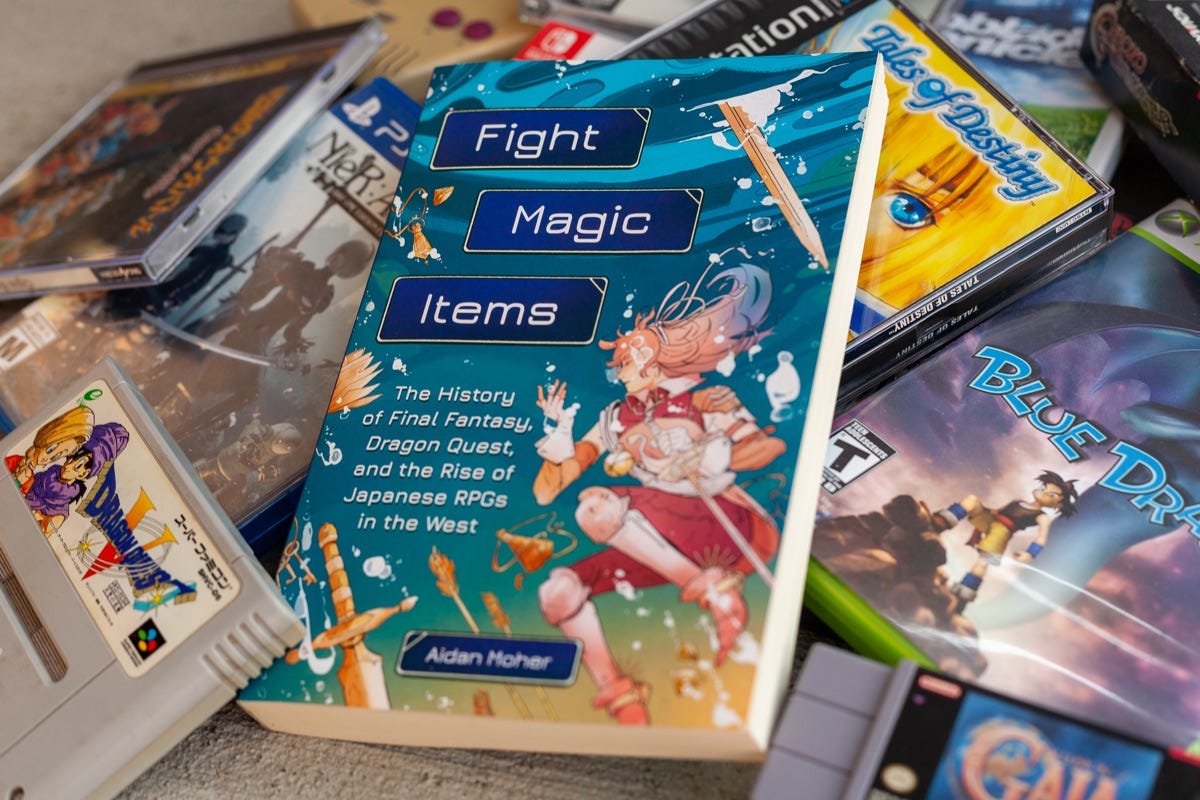

Welcome to Video Game History Week! In honour of the first anniversary of my book Fight, Magic, Items: The History of Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest, and the Rise of Japanese RPGs in the West, Astrolabe is celebrating video game history with a plethora of stories, features, lists, and interviews about video games, the people who make them, and the people who write about them.

Journey to the West: JRPGs Leave Home

Like the peasants-turned-heroes in so many of their most famous titles, JRPGs leveled up at home, but then set forth on a journey that would eventually take them across vast oceans and into the unfamiliar terrain and cultures of far-off nations.

After saving the princess of Cornelia, the king rewards Final Fantasy’s heroes by granting access to a newly restored bridge north of the castle. Beyond the bridge are broader fields, tantalizing treasures, and new adventures—a whole world to explore. But it also invited greater risks, stronger monsters, and paths to victory fraught with conflicts unlike anything the hero Erdrick had experienced before.

When Minoru Arakawa and his young family arrived in Vancouver, British Columbia, in 1977, his wife, Yoko, was a light smoker. Daughter to the famously prickly Hiroshi Yamauchi, Yoko initially protested the move to Canada, but her husband’s ambitions landed him in charge of a one-million-dollar condominium development project in the coastal Canadian city, and she begrudgingly followed him.

Winning the Nintendo president’s approval had been an uphill battle, but the struggle with his father-in-law prepared Arakawa for the challenge ahead as he moved his family overseas. Meanwhile, Nintendo had their sights set on the vast audience of American gamers who were going hot and heavy for home consoles from Atari, Magnavox, and Mattel.

With just two suitcases in tow, Arakawa checked his family into a Vancouver hotel, then hauled them next door to a Denny’s family restaurant. It was there Yoko had her first taste of the North American lifestyle. Literally. “If this is America,” she told her husband, “I have made a big mistake.”

Soon, Yoko was smoking three packs a day and grieving for her family’s future. “Frequently, she considered using the credit card her father had given her for emergencies to buy tickets home for herself and her daughter,” wrote David Sheff in Game Over: How Nintendo Conquered The World.

Yoko was mortified when her father tapped Arakawa to run Nintendo’s new American division out of New York City. Despite her desire to remain in Japan, she actually wanted nothing to do with her father’s company. “Her father was married to the business,” wrote Sheff. “He brought home all his anger and frustration when things were going badly . . . [and] blamed Nintendo for his chronic stomachaches. Throughout her childhood, the family had waited at home for him in the evenings, fearful of his moods. ‘We were all shaken by him,’ she remembers. ‘We all suffered.’”

Sadly, once again, Yoko lost out, and Arakawa took the job. They soon left Vancouver for a cross-country road trip on May 18, 1980—the same day Washington State’s Mount St. Helens erupted. Looking back on it now, it almost seems like a prophetic omen of Nintendo’s explosive growth in the West under Arakawa’s guiding hand.

With Yoko’s help as Nintendo of America’s first employee, Arakawa operated Nintendo of America out of a Manhattan office and largely focused on importing arcade titles created by the company’s Japanese division. There were many ups and downs, but their first big test came when one of the games, Radar Scope, failed to catch on with US audiences; now Arakawa suddenly had a warehouse full of unsellable cabinets. Cleverly, he, Yoko, and the rest of the small Nintendo of America team pulled up their shirtsleeves and converted Radar Scope into a new game from a young wunderkind named Shigeru Miyamoto. That game was Donkey Kong. Thanks to their out-of-the-box thinking, Nintendo of America began releasing Donkey Kong to American arcades and bars in 1981 to immense popularity and financial success.

Just a couple of years later, in 1983, the American gaming market crashed, its bubble burst by scads of low-quality games being released for the Atari 2600 and similar consoles. One of the most famous stories from this time tells of Atari dumping copies of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial in a New Mexico landfill because they couldn’t even give copies away. This sent companies like Atari spiraling, but would open the door for Nintendo to swoop in and fill the vacuum with their Eastern take on home consoles. By 1985, Arakawa found himself at the epicenter of the video game revival in the United States thanks to Nintendo’s sudden arcade success and the release of the Japanese company’s first home console: a rebranded and remodeled Famicom called the Nintendo Entertainment System, or NES as it was more commonly known.

Driven by the surging success of Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy in Japan, Arakawa saw potential for JRPGs to find a similar success in the United States. It was, after all, the home of the RPGs that had inspired Horii and Sakaguchi to create their takes on the genre in the first place. So, under the purview of a Nintendo employee named Satoru Iwata, Dragon Quest finally saw a North American release in August 1989, over three years after its original Japanese release and just months before that of the fourth installment. Though, thanks to a copyright dispute, it sported a new name: Dragon Warrior.1

The delay between the Japanese and North American releases allowed Nintendo and Enix to improve the graphics and add quality-of-life features like a cutting-edge battery-powered save system instead of having to use passwords as Japanese players had to retrieve their progress. To help Dragon Warrior live up to Arakawa’s big expectations, Nintendo heavily promoted it in their flagship magazine, Nintendo Power. Despite these best efforts, though, the game received a limp three out of five review from the magazine and walked away empty-handed during the annual yearend awards.

In a lot of ways, the United States’ response to Dragon Warrior was similar to my experience picking up Final Fantasy Legend II on the Game Boy. Why put up with its aged graphics, mediocre sound, and clunky, slow-paced gameplay when you could take down Dr. Wily in Mega Man 2 or fight through the sewers of New York City in Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles—both of which were released for the NES at the same time as the iconic JRPG? In fact, a large part of Dragon Warrior’s lacking release could be traced back to Nintendo’s focus on action platforms like Super Mario Bros., which had home console gamers looking for challenging gameplay, bright graphics, and arcade-style action. “Looking back on Nintendo’s push, it’s not hard to understand why all those Dragon Warrior cartridges wound up languishing in living rooms,” said Nadia Oxford for USgamer. “Novel as it was, Dragon Warrior was already arcane and dusty by the time it arrived.” So, while Dragon Quest took Japan by storm, Dragon Warrior limped out of the gate in North America.

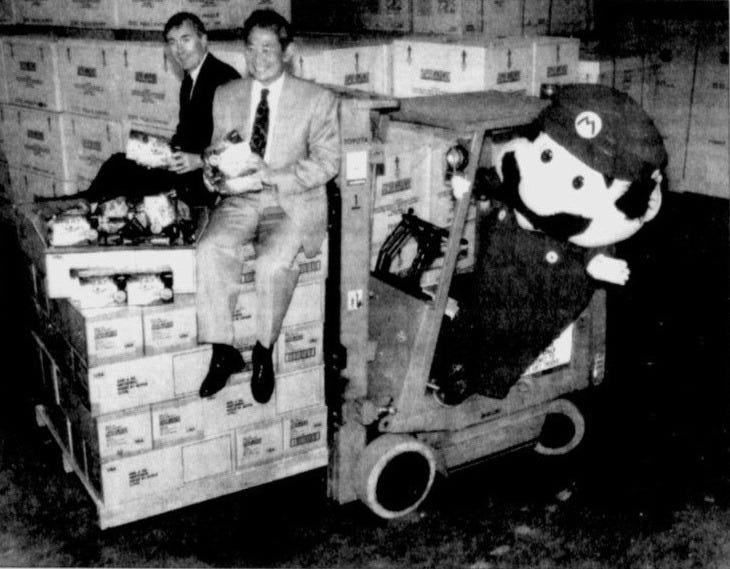

With cartridges piling up, Nintendo started giving away copies of Dragon Warrior with every Nintendo Power subscription. “Certainly, a better fate for those carts than forming a fascinating new stratum of the New Mexico bedrock,” said Jeremy Parish, “but quite the ignominious end for what should have been the next big thing.”

Giving away a $50 game and a full strategy guide to over half-a-million new subscribers2 for the cost of a $20 subscription wasn’t a pretty strategy for Nintendo, but it worked. A free game is a free game, after all. And for many kids, who only got one or two new games a year, especially ones that were as lengthy as Dragon Warrior, the game was now a very special one. Nintendo eventually moved 1.5 million copies of Dragon Warrior in North America—a necessary gamble that helped the game eventually find its hard-fought and passionate audience.

With Arakawa trying to drive the JRPG train full speed into North America, Nintendo decided to also publish Final Fantasy in July 1990—almost a full year after Dragon Warrior. Despite its competitor’s lackluster release, Final Fantasy sold about 700,000 units . . . without Nintendo Power having to hand-deliver copies. In fact, it sold more copies in the United States than at its Japanese launch. As successful as the first game was right off the bat, it was too late for the sequels to make their way overseas. Though all four of the 8-bit Dragon Quest games received English localizations, Final Fantasy II and III3 remained in Japan as Square turned its eyes to Nintendo’s upcoming 16-bit console, the Super NES, for its next big push in North America.

Ys I: Ancient Ys Vanished (1987, PC-8801)

Publisher: Nihon Falcom

Key Staff: Masaya Hashimoto, Tomoyoshi Miyazaki

With series like Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest focusing on story, Hashimoto’s Ancient Ys Vanished put combat and exploration front and center. Oddly, the player didn’t attack by swinging a weapon via button press, but by bumping into enemies. Damage was determined by the hero Adol Christin’s positioning and orientation relative to the enemy.That same year, Phantasy Star II released on Sega’s new Genesis console and racked up industry awards, including Video Games & Computer Entertainment’s “Game of the Year” and tied with the TurboGrafx-16’s Ys I & II for “Best Adventure Game.”4 Though these new JRPGs were successful and gaining traction with the press and players, it was a markedly slower burn than in Japan. Arakawa knew JRPGs had potential in the West, but there were still many unknowns to grapple with. Were they being choked out by the very RPGs that inspired them? Or did the larger Western audience just have different tastes than the typical Japanese gamer?

According to the “architect” of the PlayStation’s success, Ken Kutaragi, whose console would play a huge role in the eventual Western popularization of JRPGs, the slow success was due to how the technology at the time conveyed the game world and playing experience. Until the mid-’90s, games weren’t widely enjoyed by consumers of all ages or gender, according to Kutaragi, who blamed this on “grainy” 2D graphics and overly simple visuals. The compromises required to create complex games like JRPGs with pixel-based graphics made it challenging for them to find cross-cultural success. “For this reason,” Kutaragi told The Washington Post in 2020, “Japanese RPGs did not perform very well abroad, and western games didn’t do well in Japan either.”

Adding to this challenge in the ’90s was that Japanese creators like Sakaguchi and Horii created their games specifically for a Japanese audience. While titles like Super Mario Bros. and racing games were developed with a broad audience in mind, Kutaragi said, “Final Fantasy includes an abundance of Japanese elements, in terms of character portrayal and animation, battle sequences, and dialogue.”

For some gamers like myself, Kutaragi’s points about abstraction were a major part of the appeal of JRPGs. I bounced off them at first, but when I returned a few years later, I was enthralled by the way their relatively simple mechanics and graphics allowed me to imprint myself on the story and fictional universe—the opposite of the visceral focus on positive feedback loops used by most games at the time.

In hindsight, though, it’s easy to see why Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest failed to catch on with most of the Western gaming audience. These were gamers looking for things you could pick up and play with friends, beat a few levels, finish a few rounds, and share a laugh. They wanted the action-packed frenzy of Final Fight in arcades or Dr. Mario’s cerebral puzzle-solving and high scores. And there on the horizon? Nintendo’s new console, the Super NES and all its promises of bigger, brighter, faster games. Compared to magazine screenshots of Super Mario World and F-Zero, Final Fantasy looked like old news.

With little time to sit and ponder the differences in audiences and cultures, creators like Kodama, Sakaguchi, and Horii were starting work on the 16-bit adventures that would kick off the genre’s first golden age.

Excerpt from Aidan Moher's Fight, Magic, Items reprinted by permission of the author and Running Press.About Fight, Magic, Items: The History of Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest, and the Rise of Japanese RPGs in the West

Take a journey through the history of Japanese role-playing games—from the creators who built it, the games that defined it, and the stories that transformed pop culture and continue to capture the imaginations of millions of fans to this day.

The Japanese roleplaying game (JRPG) genre is one that is known for bold, unforgettable characters; rich stories, and some of the most iconic and beloved games in the industry. Inspired by early western RPGs and introducing technology and artistic styles that pushed the boundaries of what video games could be, this genre is responsible for creating some of the most complex, bold, and beloved games in history—and it has the fanbase to prove it. In Fight, Magic, Items, Aidan Moher guides readers through the fascinating history of JRPGs, exploring the technical challenges, distinct narrative and artistic visions, and creative rivalries that fueled the creation of countless iconic games and their quest to become the best, not only in Japan, but in North America, too.

Moher starts with the origin stories of two classic Nintendo titles, Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest, and immerses readers in the world of JRPGs, following the interconnected history from through the lens of their creators and their stories full of hope, risk, and pixels, from the tiny teams and almost impossible schedules that built the foundations of the Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest franchises; Reiko Kodama pushing the narrative and genre boundaries with Phantasy Star; the unexpected team up between Horii and Sakaguchi to create Chrono Trigger; or the unique mashup of classic Disney with Final Fantasy coolness in Kingdom Hearts. Filled with firsthand interviews and behind-the-scenes looks into the development, reception, and influence of JRPGs, Fight, Magic, Items captures the evolution of the genre and why it continues to grab us, decades after those first iconic pixelated games released.

Learn more on the Fight, Magic, Items website!

Support

There are lots of ways to support Astrolabe and my other work. Check ‘em out!

Keep In Touch

Enjoy Astrolabe? Want more SFF and retro gaming goodies? You can find me on Twitter and my website.

Credits

Astrolabe banner photo by Shot by Cerqueira on Unsplash

This naming discrepancy lasted until Dragon Quest VIII: Journey of the Cursed King sixteen years later. ↩

Plus an undocumented number of those already subscribed or who re-subscribed to get the game. ↩

Not to be confused with the Final Fantasy II and III released in English for the Super NES. With Final Fantasy’s late Western release, Square skipped its 8-bit sequels. Not wanting to confuse American gamers by jumping from Final Fantasy to Final Fantasy IV, they forged ahead with a regional naming system. Western gamers got three mainline games (Final Fantasy, Final Fantasy IV, and Final Fantasy VI) released as Final Fantasy, Final Fantasy II, and Final Fantasy III, before Square finally squared up (ahem) the naming conventions just in time for 1997’s massive hit Final Fantasy VII. It was all a bit much. ↩

At the time, Video Games & Computer Entertainment didn’t even have a “Best RPG” category for their awards—a clear indication of how little presence the genre had with the North American audience at the time. Electronic Gaming Monthly did have a “Best RPG” category, but Phantasy Star II lost out to Ys I & II. ↩